Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication

– Leonardo Da Vinci

There’s plenty of tests frameworks out there, but I am often left disgruntled by their sheer amount of complexity, and by lack of uniformity of the tests/inability to programmatically manipulate them.

This article presents what is arguably the simplest test framework for function-based code: each test is basically about ensuring that applying a function on some input yields the expected output.

All tests have the exact same format, and can be stored in an array, and thus altered programmatically/systematically. Sophisticated cases (e.g. objects, side effects) can be managed by involving a few ad-hoc lambdas to alter the input/output so as to fit in this format.

In the end, it’s costless to:

- implement;

- audit;

- add to an existing codebase, even alongside an already existing test framework;

- migrate away from in the future (perhaps not costless, but definitely easier than your usual tests);

And, most importantly, makes it effortless to write batches of straightforward tests in almost any language. Its main requirement is for the implementation language to easily allow deep-comparison; in the worst cases, this can often be achieved by comparing JSON dumps, or more generally, text dumps.

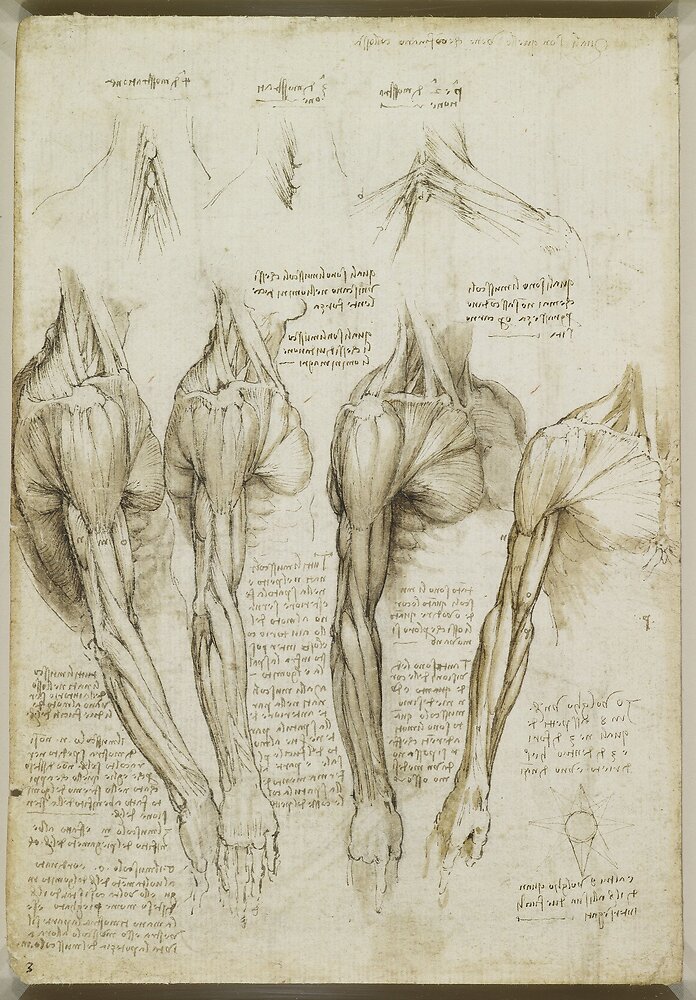

Superficial anatomy of the arm; mostly side/front view

by

Leonardo da Vinci

Sample implementation: JS, Perl, Go, (Nix)

Starting with a JS and a Perl version:

/**

* Dump some data to the console in JSON

*

* @param{Array.<any>} xs - objects to be dumped

* @returns{void} - all xs would have been dumped to console.

*/

function dump(...xs) { ... }

/**

* Deep comparison.

*

* NOTE: Exhaustive enough for our purposes.

*

* @param{any} a - first object to compare.

* @param{any} b - second object to compare.

* @returns{boolean} - true if a and b are equals, false otherwise.

*/

function dcmp(a, b) {

...

}

/**

* Run a single test.

*

* NOTE: we're a bit lazy when comparing to error. Perhaps

* we could add an additional entry for that instead of using

* expected. This is of little practical importance for now.

*

* @this{any} -

* @param{function} f - function to test

* @param{Array.<any>} args - array of arguments for f

* @param{any} expected - expected value for f(args)

* @param{string} descr - test description

* @param{string|undefined} error - expected error (exception)

* @returns{boolean} - true if test executed successfully

*

* In case of failure, got/expected are dumped as JSON on the console.

*/

function run1(f, args, expected, descr, error) {

var got;

try {

got = f.apply(this, args);

} catch(e) {

console.log(e);

got = e.toString();

expected = error || "<!no error were expected!>";

}

var ok = dcmp(got, expected);

console.log("["+(ok ? "OK" : "KO")+"] "+f.name+": "+descr);

if (!ok) {

console.log("Got:", );

dump(got);

console.log("Expected: ");

dump(expected);

}

return ok;

}

/**

* Run multiple tests, stopping on failure.

*

* @param{Array.<Test>} tests - tests to run

* @returns{boolean} - true iff all tests were run successfully

*/

function run(tests) {

return tests.reduce(

/** @type{(ok : boolean, t : Test) => boolean} */

function(ok, t) {

return ok && run1(t.f, t.args, t.expected, t.descr, t.error);

},

true

);

}package FTests;

use strict;

use warnings;

# Test::Deep::cmp_deeply() would be slightly better

# than Test::More::is_deeply(), but Test::More comes

# with a default perl(1) installation.

use Test::More;

use B;

# Retrieve a name for a coderef.

#

# See https://stackoverflow.com/a/7419346

#

# Input:

# $_[0] : coderef

# Output:

# string, generally module::fn

sub getsubname {

...

}

# A test is encoded as a hashref containing:

#

# {

# "f" => \&function_pointer,

# "fn" => $optional_function_name,

# "args" => $arrayref_holding_input_arguments,

# "expected" => $expected_output_values

# "descr" => "Test description, string",

# }

# Run a single test.

#

# Input:

# $_[0] : hashref describing the test (see above)

# Output:

# Boolean: 1 if the test was successfully executed,

# 0 otherwise.

#

# May die().

sub run1 {

my ($test) = @_;

my (

$f,

$fn,

$args,

$expected,

$descr,

) = @{$test}{qw(f fn args expected descr)};

my $n = $fn || FTests::getsubname($f);

# NOTE: We could manage exceptions

return Test::More::is_deeply(

$f->(@$args),

$expected,

sprintf("% -35s: %s", $n, $descr),

);

}

# Run a list of tests in order, stopping in case of

# failure.

#

# Input:

# $_[0] : arrayref of tests

# Output:

# Boolean: 1 if all tests were successfully executed,

# 0 otherwise.

#

# May die().

sub run {

my ($tests) = @_;

foreach my $test (@$tests) {

return 0 unless(FTests::run1($test));

}

return 1;

}Then, here’s a third implementation in Go, more tedious because of the static typing. As for the Perl version, it relies on a tiny subset of its standard testing module:

package main

import (

"testing"

"reflect"

"strings"

"runtime"

"fmt"

"encoding/json" // pretty-printing

)

type test struct {

name string

fun interface{}

args []interface{}

expected []interface{}

}

func getFn(f interface{}) string {

xs := strings.Split((runtime.FuncForPC(reflect.ValueOf(f).Pointer()).Name()), ".")

return xs[len(xs)-1]

}

func doTest(t *testing.T, f interface{}, args []interface{}, expected []interface{}) {

// []interface{} -> []reflect.Value

var vargs []reflect.Value

for _, v := range args {

vargs = append(vargs, reflect.ValueOf(v))

}

got := reflect.ValueOf(f).Call(vargs)

// []reflect.Value -> []interface{}

var igot []interface{}

for _, v := range got {

igot = append(igot, v.Interface())

}

if !reflect.DeepEqual(igot, expected) {

sgot, err := json.MarshalIndent(igot, "", "\t")

if err != nil {

sgot = []byte(fmt.Sprintf("%+v (%s)", igot, err))

}

sexp, err := json.MarshalIndent(expected, "", "\t")

if err != nil {

sexp = []byte(fmt.Sprintf("%+v (%s)", expected, err))

}

// meh, error are printed as {} with JSON.

fmt.Printf("got: '%s', expected: '%s'", igot, expected)

t.Fatalf("got: '%s', expected: '%s'", sgot, sexp)

}

}

func doTests(t *testing.T, tests []test) {

for _, test := range tests {

t.Run(fmt.Sprintf("%s()/%s", getFn(test.fun), test.name), func(t *testing.T) {

doTest(t, test.fun, test.args, test.expected)

})

}

}Exercise: Write a Nix version.

Solution:[+]Exercise: Write a Python version.

Exercise: The JS version does manage exceptions to some degree. Add exceptions support to the Perl version.

Exercise: Implement and test the JS’s dcmp() function. You can

find a few incomplete tests in the following section.

Exercise: Write a sh(1) version.

Solution:[+]Exercise: Think about some implementation options for a C version.

Solution:[+]

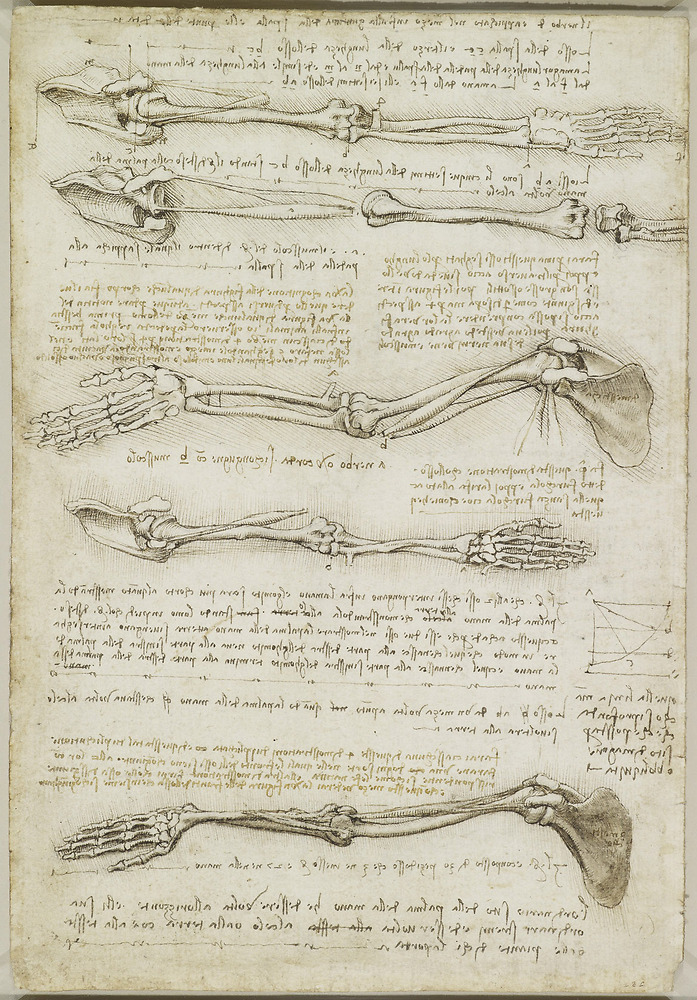

Bones of the arms (c. 1510)

by

Leonardo da Vinci

Example usage: JS, Perl

import * as FTests from '../modules/ftests.js'

FTests.run([

/*

* dcmp()

*/

{

f : Ftests.dcmp,

args : [1, 1],

expected : true,

descr : "Integers, equals",

},

{

f : Ftests.dcmp,

args : [1, 2],

expected : false,

descr : "Integers, not equals",

},

...

{

f : Ftests.dcmp,

args : [{}, []],

expected : false,

descr : "Empty hash is not an array",

},

{

f : Ftests.dcmp,

args : [{}, {}],

expected : true,

descr : "Hashes, empty, equals",

},

...

{

f : Ftests.dcmp,

args : [{foo : [1, 2, [3, 1]]}, {foo : [1, 2, [3, 1]]}],

expected : true,

descr : "Deep object, equals",

},

{

f : Ftests.dcmp,

args : [{foo : [1, 2, [3, 1]]}, {foo : [1, 2, [3, 1, {}]]}],

expected : false,

descr : "Deep object, not equals",

},

]);#!/usr/bin/perl

use strict;

use warnings;

use File::Basename;

use lib File::Basename::dirname (__FILE__);

use Test::More;

use FTests;

sub id { return $_[0]; }

FTests::run([

{

"f" => sub { return $_[0]; },

"fn" => '(\\x = x)',

"args" => [1],

"expected" => 1,

"descr" => "(\\x = x) 1",

},

{

"f" => \&id,

"args" => [{foo=>"bar"}],

"expected" => {foo=>"bar"},

"descr" => "id({foo=>'bar'}) = {foo=>'bar'}",

},

{

"f" => \&FTests::run,

"args" => [[{

"f" => \&id,

"fn" => "FTests::run([id])",

"args" => [{foo=>"baz"}],

"expected" => {foo=>"baz"},

"descr" => "id({foo=>'baz'}) = {foo=>'baz'}",

}]],

"expected" => 1,

"descr" => "going meta",

},

]);

Test::More::done_testing();Common patterns

Objects, environment alteration

Testing a method on a given object in a given state can be performed by the addition of a lambda wrapping the desired operations, for instance

function Something(state, error) {

this.state = state;

this.error = error;

this.f = (error) => {

this.error = error;

if (this.state == "init")

this.state = "started";

return "something";

}

}

function alter(o, nargs, f, args) {

var x = new (Function.prototype.bind.apply(Something, [{}, ...nargs]));

var y = x[f].apply(x, args);

return {

'result' : y,

'state' : x.state,

};

}

alter(Something, ["init", ""], "f", ["nothing"]);

// {result: 'something', state: 'started'}

Global environment alteration can be managed similarly:

var global = 0;

function something(x, y) {

global = x + y;

return x-y;

}

function alter(f, args) {

var x = f.apply({}, args)

return [x, global];

}

alter(something, [2, 3]);

// [-1, 5]

Pointer/reference arguments

Some functions can easily alter their arguments, especially for pointer-based types (array, hashes, etc.). Testing their alteration is better performed if the related functions return such altered arguments.

function something(xs) {

if (xs.length > 0)

xs[0]++;

return xs;

}This could also be wrapped by lambdas, as previously demonstrated.

function something(xs) {

if (xs.length > 0)

xs[0]++;

return 42;

}

function alter(f, args) {

var x = f.apply({}, args)

return [args, x];

}

// NOTE: single argument is an array holding two numbers

alter(something, [[2, 3]]);

// [[3, 3], 42]

Exercise: How would you test the following function, without modifying its code?

function dostuff(x, y) {

return [x+y, x-y, x*y, Date.now()];

}

// e.g. dostuff(2, 3);

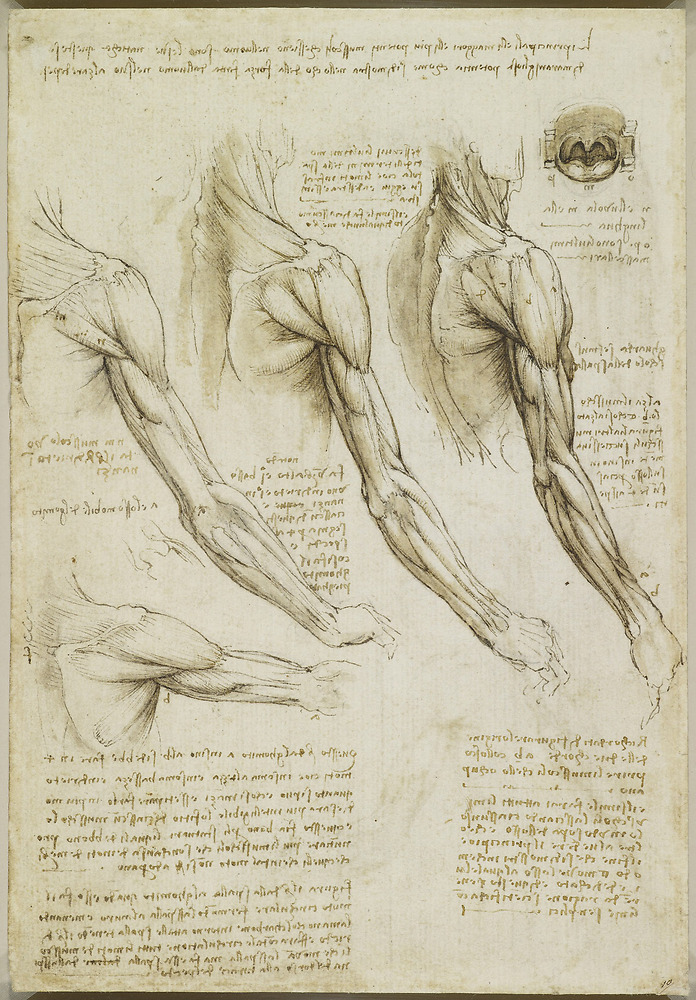

Arms, muscles of the shoulder arm and neck, back/side view

by

Leonardo da Vinci

Comments

By email, at mathieu.bivert chez: