For students willing to go the extra-mile, the following exercises can be used to foster one’s handling of material, and progressively develop the ability to draw from imagination. Bargue’s plates, because of their simplicity and diversity, make very good models for such technical drills.

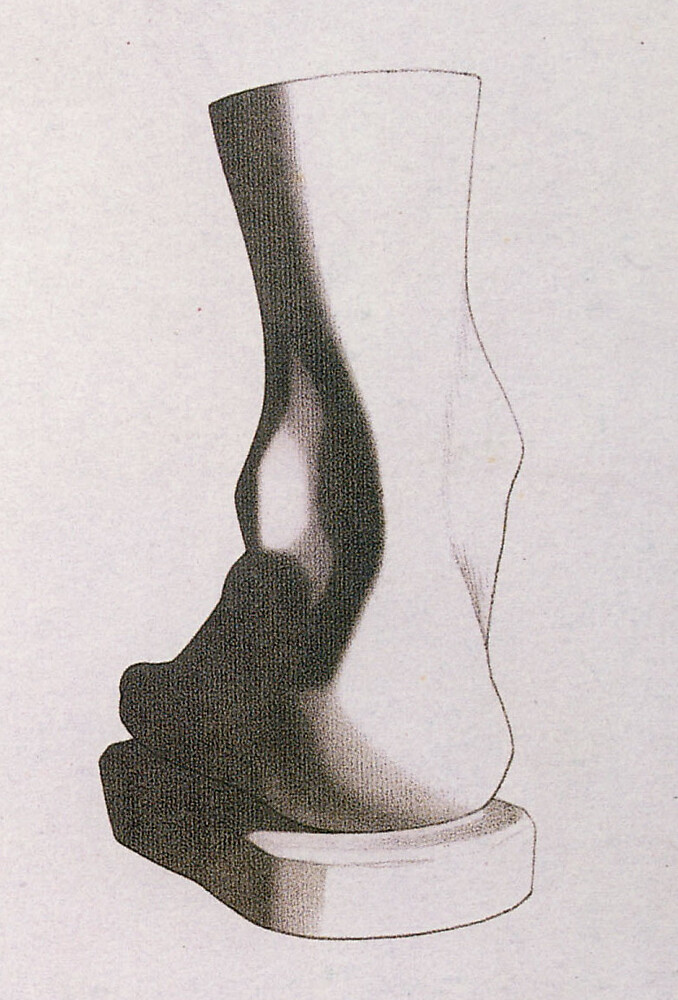

Bargue’s Plate I 5 “mirrored” copy, graphite and chalk on toned paper

by

M. Bivert

While most Westerners may know the term “gong-fu” as a synonym for some kind of Chinese martial art, it originally has a wider meaning:

Note: I haven’t (hopefully yet) practiced all the following exercises, or practiced them to their fullest extent, nor am I aware of a lot of people doing such drills. Bear in mind thought that in many disciplines, such as cooking or assembly-line work, people do definitely optimize and polish their skills to an admirable extent:

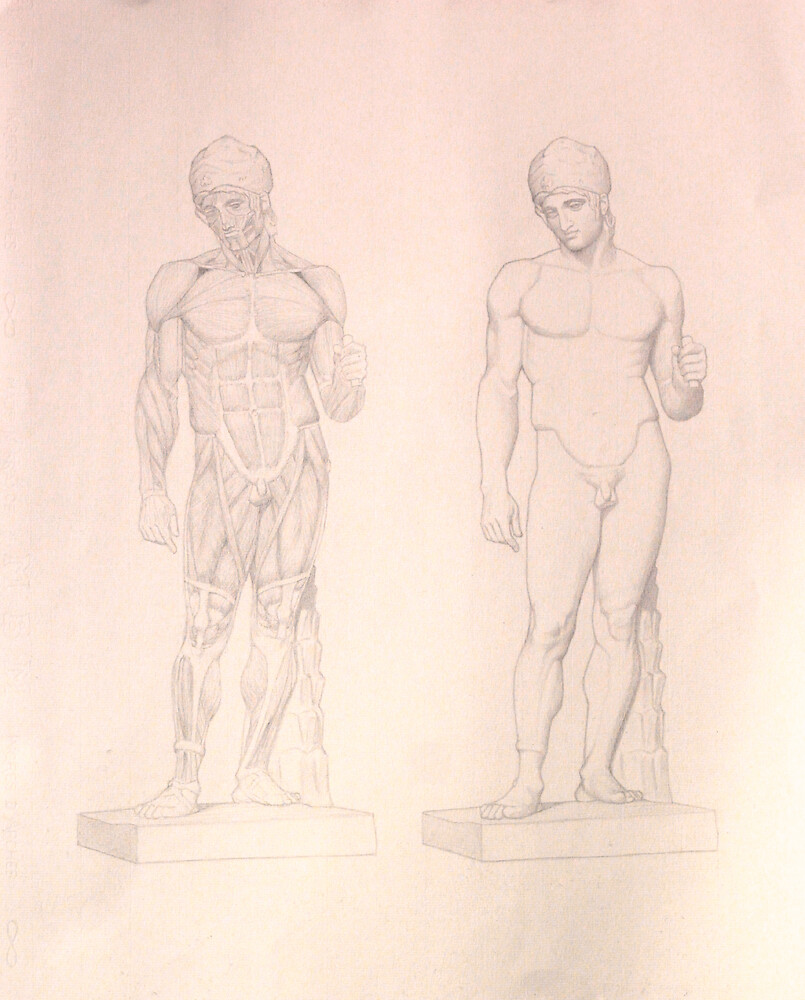

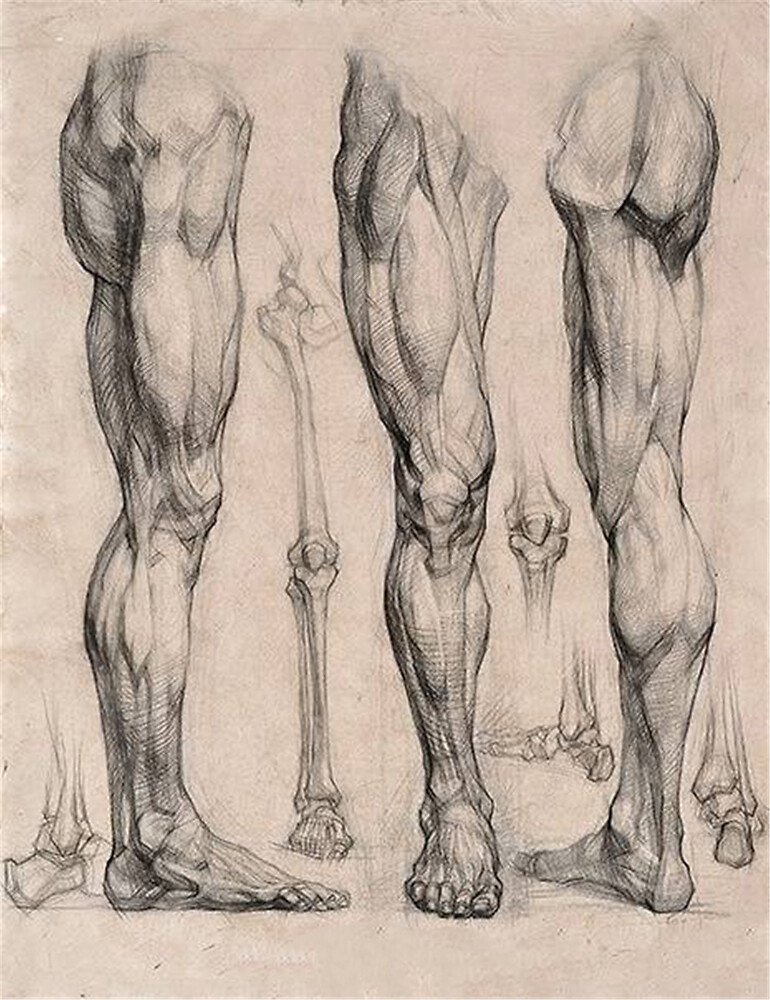

Anatomy

Because of the common double-round of volumes simplification (that is, the forms are first simplified by the sculptors, and then by Bargue; furthermore antique’s anatomy was heavily stylized) Bargue plates aren’t the easiest playground for it to explore anatomy.

But that’s precisely why they offer an interesting challenge. Anatomy study would deserve a article on its own, but to keep things short, it can be a distraction for beginners, so practice it very lightly at first, and focus on proportions and value control.

Bargue Plate I 68 master copy, “Achilles”, with an écorché, graphite on Ingres paper (Arches, 75% cotton)

by

M. Bivert

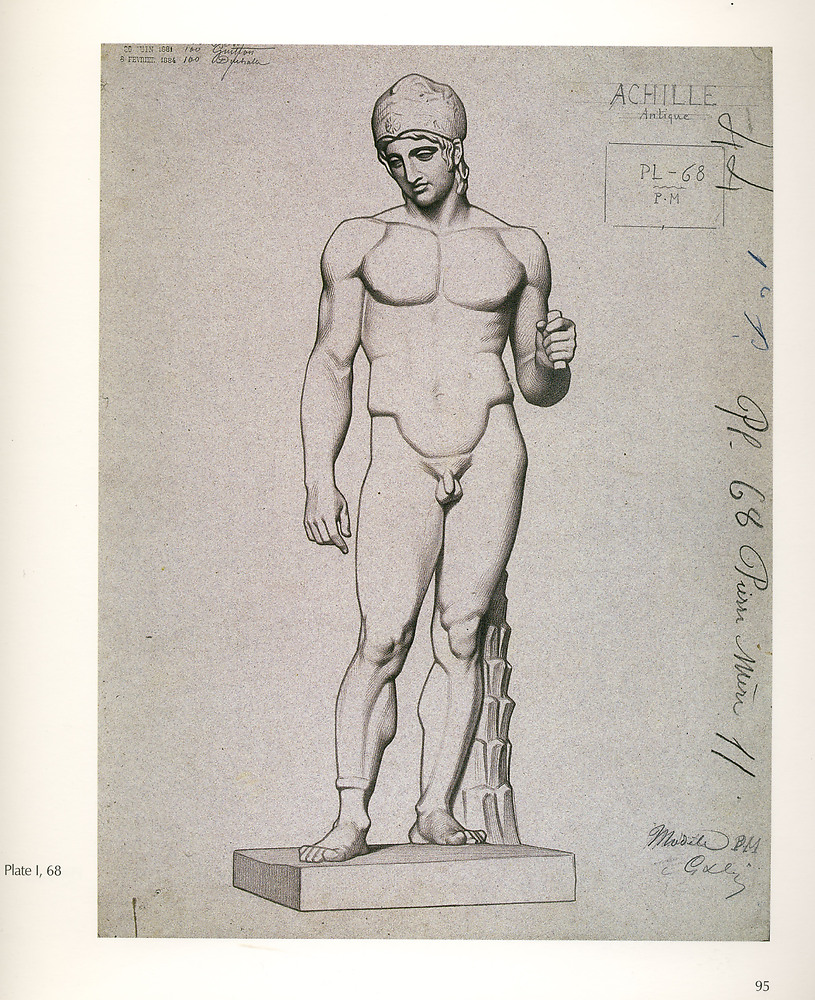

Plate I 68, “Achilles”, now thought to be Mars/Ares, see Ares Borghese and the Louvre’s page

by

Charles Bargue

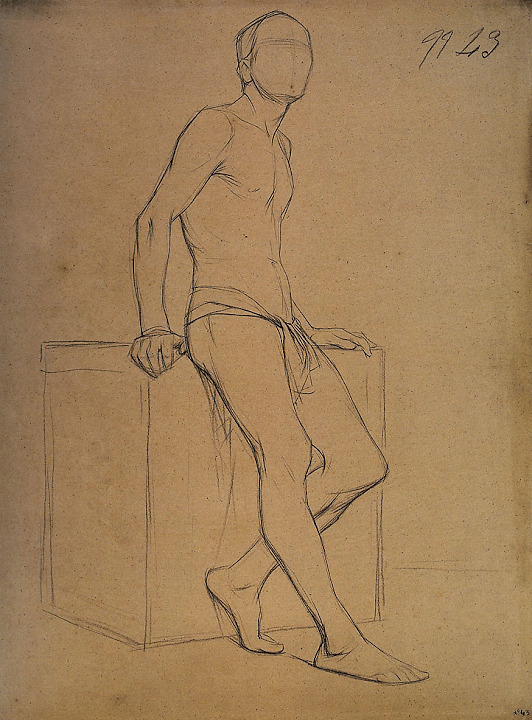

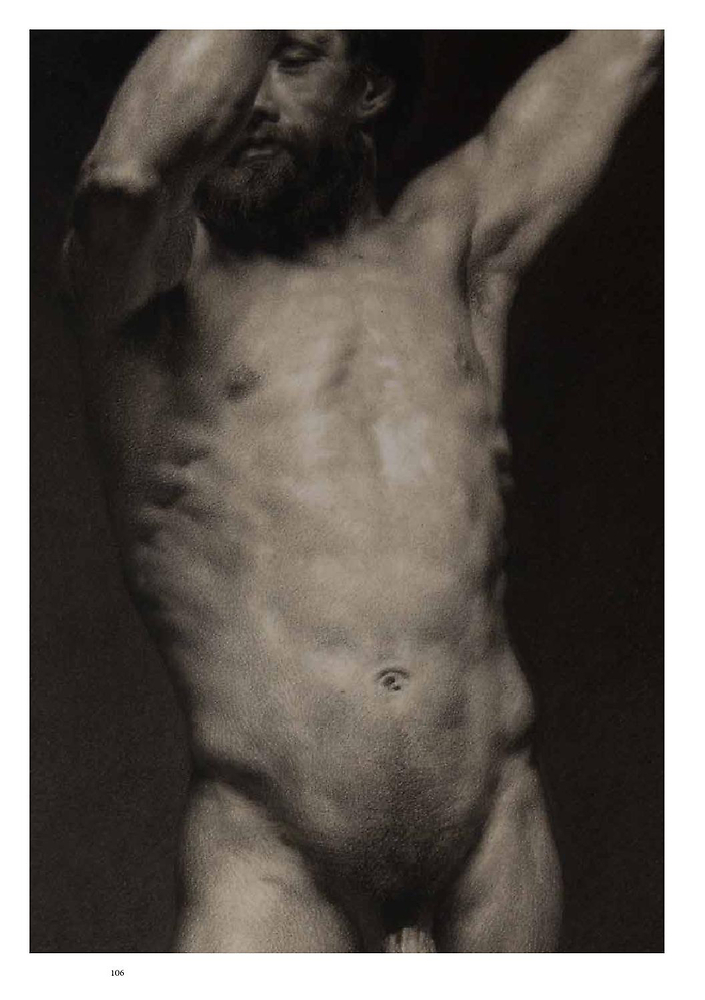

Perhaps the plate of the third section, created from a life model, would be as, if not more, interesting to study from an anatomical point of view:

Plate III 43, Man leaning against a stand, face lifted up

by

Charles Bargue

Note: It can be a good idea to compare Bargue’s drawings with more advanced, polished drawings and studies from life, such as drawings from Russian academies, where students are encouraged to strongly emphasize anatomy.

Leg anatomy study, from the Glazunov Academy (Академия И.Глазунова) through vk.com ykpx.com – likely, available for fair use

Male study, close-up, 80×60, charcoal, italian pencil, chalk, paper, 1856; compiled in Drawing Samples for Copying / Obraztsy Dlya Kopirovaniya by V.A. Mogilevtsev by П. П. Чистяков – Public domain

Memorization, inner vision development

I’ve read a story about how at some point in the history of the Russian academy, students had to work from a model located on one floor, while their easels were located on another floor.

Leonardo Da Vinci (1452 – 1519) recommended, as collected in his Treatise on painting, Chap. XXI.—Of studying in the Dark, on first waking in the Morning, and before going to sleep:

I have experienced no small benefit, when in the dark and in bed, by retracing in my mind the outlines of those forms which I had previously studied, particularly such as had appeared the most difficult to comprehend and retain; by this method they will be confirmed and treasured up in the memory.

La Scapigliata, female head, oil on panel, 27×21cm, Galleria nazionale di Parma

by

Leonardo da Vinci

Marie-Élisabeth Cavé (c. 1809 - 1883), French, contemporary of Ingres (1780 – 1867), authored a little book entitled Drawing from memory, which opens-up by a Report of the Inspector-General of Fine Arts to the Minister of the Interior, upon Madame Caves Method of Drawing, observing:

Thus, by exercising the memory of children, giving accuracy of vision and firmness of hand at the age when their organs, still tender, are docile, Madame Cave renders them better qualified for the industrial professions, makes them skilful instruments in all the trades which pertain to art.

Harold Speed (1872-1957) also emphasizes the possibility and potential of training visual memory in his The Practice and Science of Drawing, Chapter XVIII, The Visual Memory:

Just as the faculty of committing to memory long poems or plays can be developed, so can the faculty of remembering visual things. This subject has received little attention in art schools until just recently. But it is not yet so systematically done as it might be. Monsieur Lecoq de Boisbaudran in France experimented with pupils in this memory training, beginning with very simple things like the outline of a nose, and going on to more complex subjects by easy stages, with the most surprising results.

And there is no doubt that a great deal more can and should be done in this direction than is at present attempted. What students should do is to form a habit of making every day in their sketch-book drawing of something they have seen that has interested them, and that they have made some attempt at memorising. Don’t be discouraged if the results are poor and disappointing at first—you will find that by persevering your power of memory will develop and be of the greatest service to you in your after work.

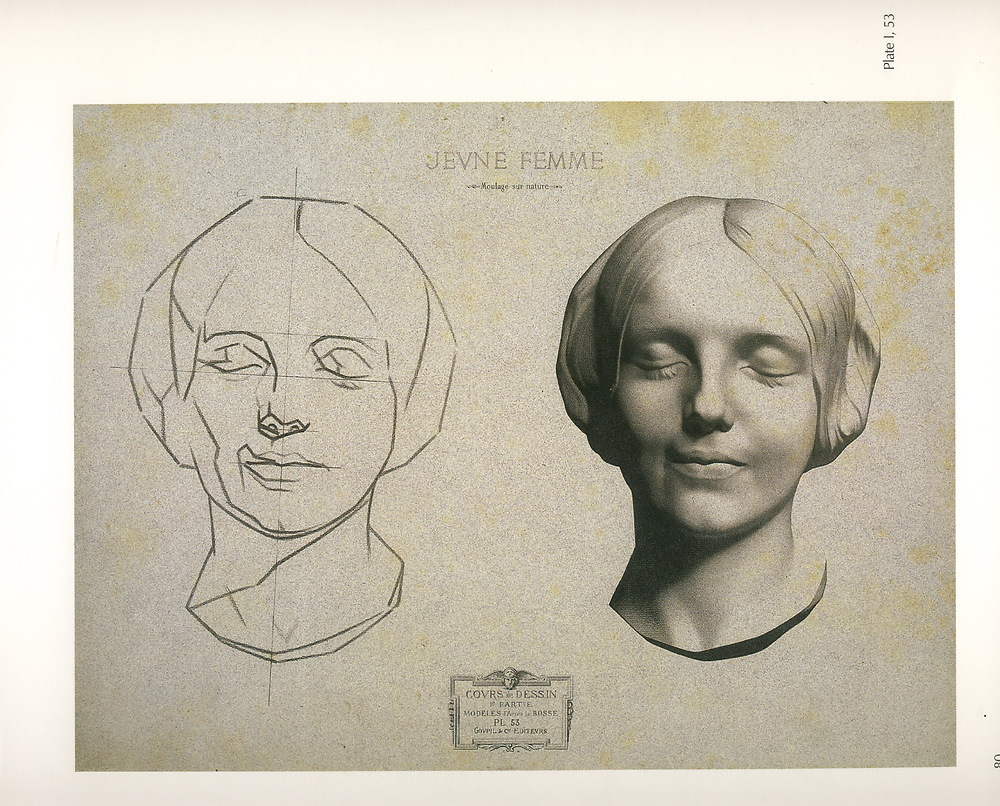

Plate I 53, Young woman life cast

by

Charles Bargue

Bargue plates, especially the simplest ones, can be used in such a way. Having great models carved in one’s brain is handy in many ways.

Note: An interesting phenomenon occurs after having spend 10h, 20h on a copy: a relatively clear visual impression of the drawing can come to mind at will, at least for a few days, without specific memory training.

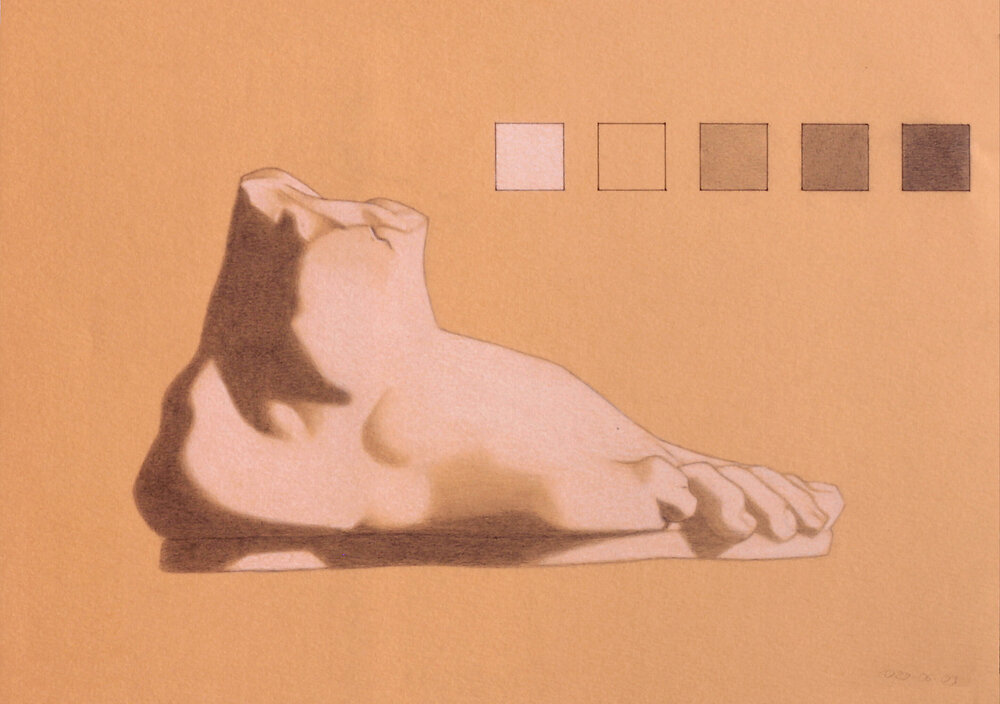

The following plate was copied from memory:

- 30min of observation one day;

- 30min of observation the next one;

- 10min of observation the next one;

- on the same day, roughly 3 to 4h of recalling drawing, with 10 more min of observation at some point

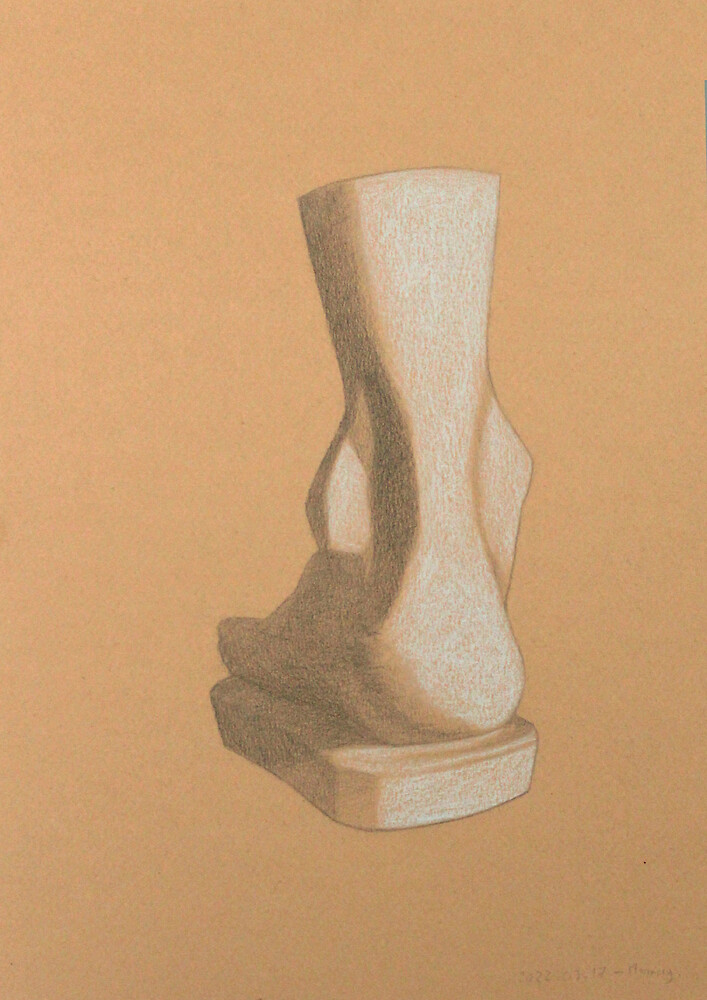

Bargue’s Plate I 6 (1), copy from memory, graphite and chalk on toned paper, A4

by

M. Bivert

Plate I 6, First heel

by

Charles Bargue

Size

Drawing on small scales presents certain advantages and certain drawbacks. So does drawing on big scales.

Contrary to what one may believe, drawing big isn’t necessarily more difficult, especially regarding proportions: it’s easy to make a 1mm or 2mm mistake; on a small scale drawing, this will jump to the eye easily, while it will remain negligible on larger scale drawings.

Hence why students are often recommended to draw on relatively big sheets. The difficulty here comes in the effort to perform the rendering, as there is more surface; this is particularly true with the common graphite-based rendering approach used for early Bargue plates.

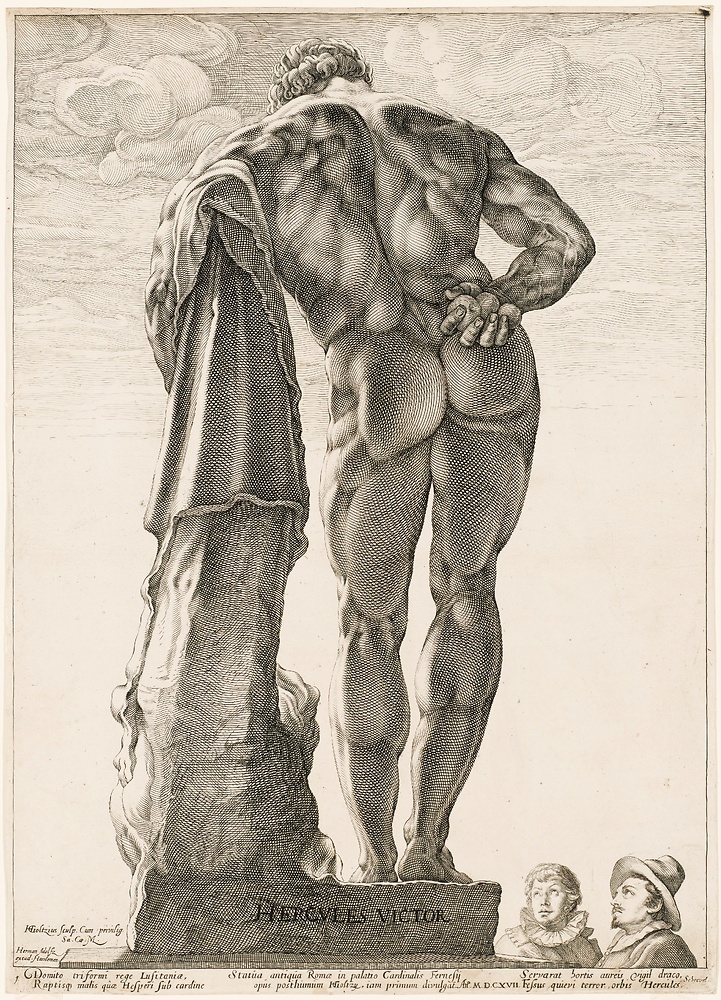

Engraving of the Farnese Hercules by Glycon, likely after a model from Lysippos

by

Hendrick Goltzius

That being said, varying the size of the drawing can help prepare students for various kind of difficulties that may occur later in professional settings, and also experiment with the impact of the size on composition.

For instance, heads are typically drawn at least a little bit smaller than their real life size. This is because, as we’ve already mentioned regarding perspective and stands, when we observe a drawing, we do so at a distance. If heads aren’t drawn slightly smaller, they will quickly feel gigantic and unappealing.

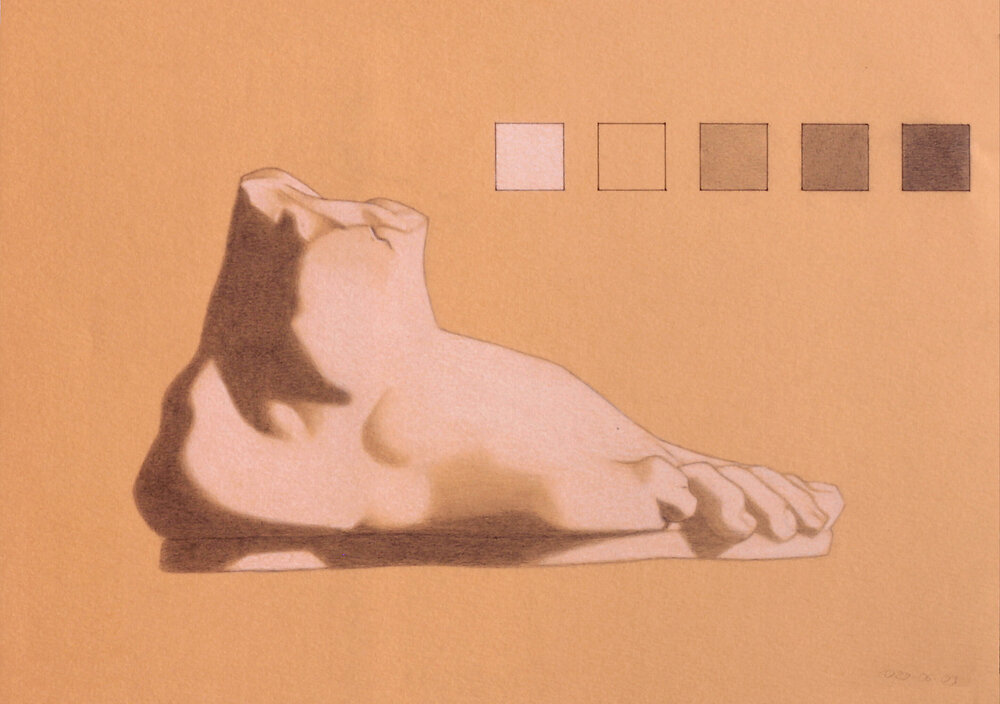

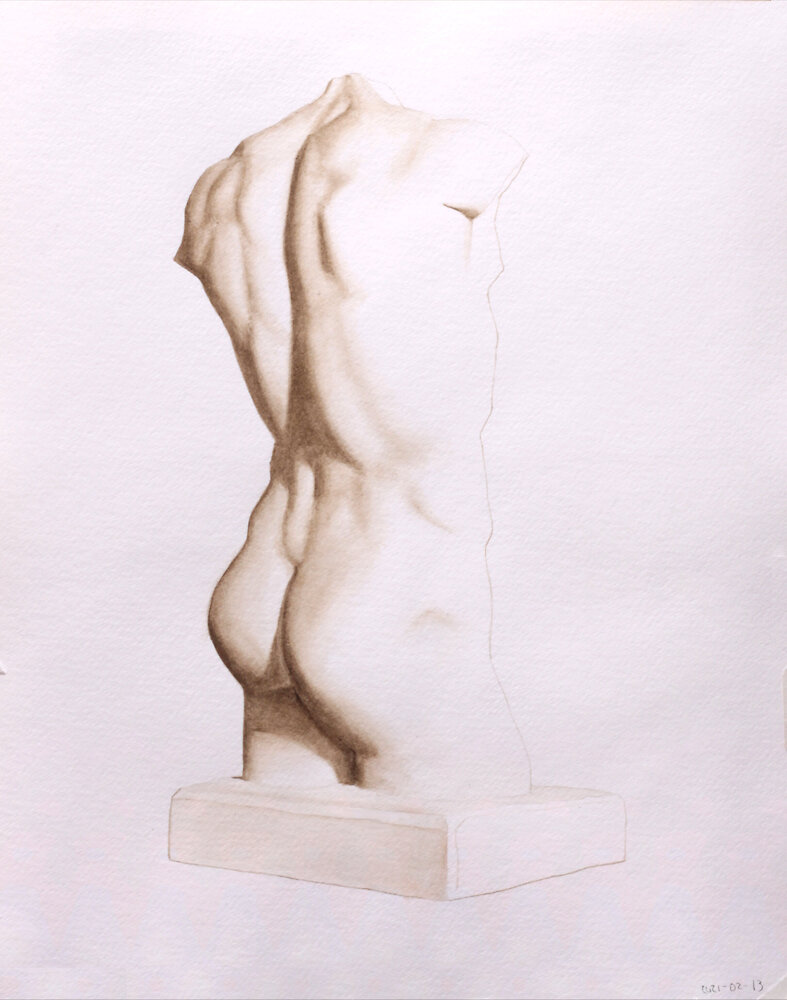

Toned paper, value compression/translation

Generally speaking, Bargue plates are to be reproduced with exactitude. Yet, practically speaking, either because of material, because of composition requirements, artists often need to interpret the value range.

Using toned paper, compressing/decompressing or translating the value range all can be used to train artists to develop interpretation of the value range, and to subdue it to æsthetical needs.

Bargue’s Plate I 5 “mirrored” copy, graphite and chalk on toned paper

by

M. Bivert

Difficult environment

Often when drawing, we take good care of being in a comfortable setting. But in practice, things can get uncomfortable for various reasons: this is typical when doing plein-air landscapes, or museum studies.

Some athletes train on high altitudes: the relative lack of oxygen makes exercising more difficult, and when coming back to normal conditions, exercising will feel and appear easier by comparison.

Hence why making drawing exercising conditions a bit more difficult (remember those poor Russian students) can be beneficial, think, mirroring, drawing in a moving vehicle, in busy places, isolating one light source from many in a museum, etc.

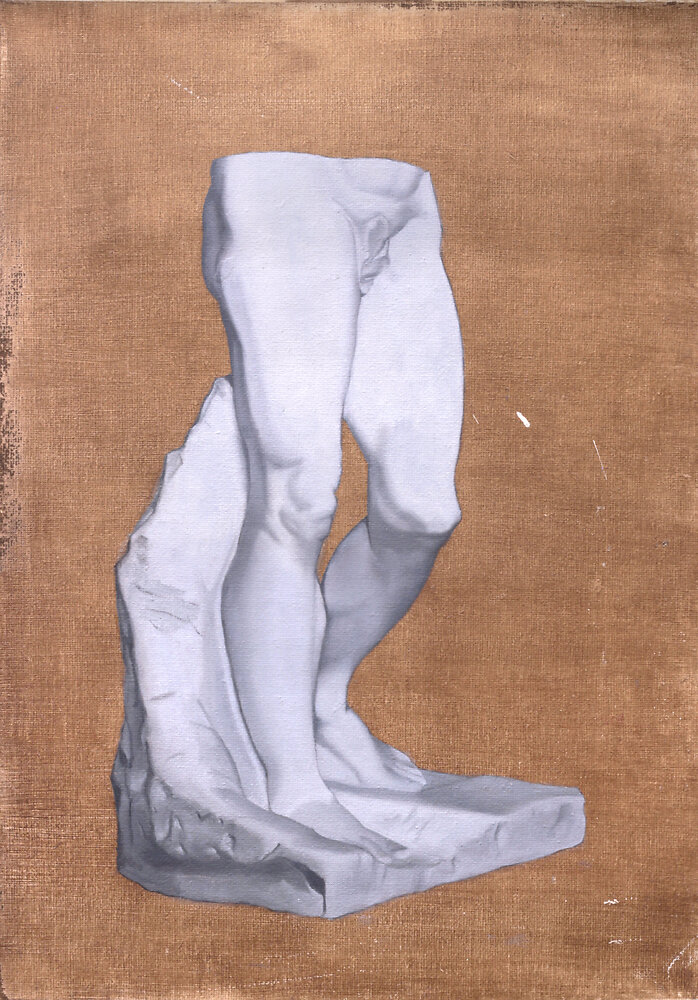

Material diversity

As we’ve already mentioned, Bargue plates are great for exercising control over one’s material. Thus, they are a perfect playground to efficiently experiment with new materials.

This includes pretty much anything, ranging from oils, watercolors, pastels, silverpoint, etc. Getting something right monochromatically often is the most difficult part.

Bargue’s plate I-30 (“Legs of the dying slave”) copy. Black and white oils on a burnt umber washed canvas

by

M. Bivert

Toward imagination

A few more suggestions:

- inventing colors (starting from dull, “temperature” palettes, e.g. brown/black/white, or orange-ish brown/blue/white);

- changing light directions;

- turning the model/point of view;

- etc.

Ambidexterity

Ambidexterity is an interesting skill to develop for two main reasons.

The first one, is that, if you practice it later, it will help you empathize again with the difficulty of being untrained, thus helping you connect with beginners.

But more perhaps importantly, some marks are naturally easier to make with one hand than the other, like hatching on diagonal from top-right to bottom-left is trivial with a right hand, but not so with a left hand, and vice-versa.

Final notes for self-taught students

This article is long and somehow dense. From experience, it’s unlikely to be able to fully digest everything at once, thus reading it multiple times while exercising your skills on the side is likely to be mandatory. It took me a few years of practice, observation and learning after established artists to collect all of this.

You’re likely to encounter a few keystones in your journey, maybe in a different order:

- rough copies, proportion and rendering wise, poor material control, unable to work on the same plate for enough time to delve into subtleties or obtain anything refined;

- better appreciation of proportions;

- attention to subtle nuances of tones, hatching;

- better material control so as to render such nuances;

- at some point, able to make a close to perfect copy with comparative measurements, with excellent proportions, material control, nuances, taking 40h if need be, and likely, stopping yourself knowing you could spend more time to refine some aspects.

- you should then progressively realize that making perfect copies is limiting when drawing from life, or when trying to actually make a living out of art. You may then sacrifice a bit in accuracy for speed or a looser technique, and starts to appreciate the difference between a copy/study and a finished piece of art.

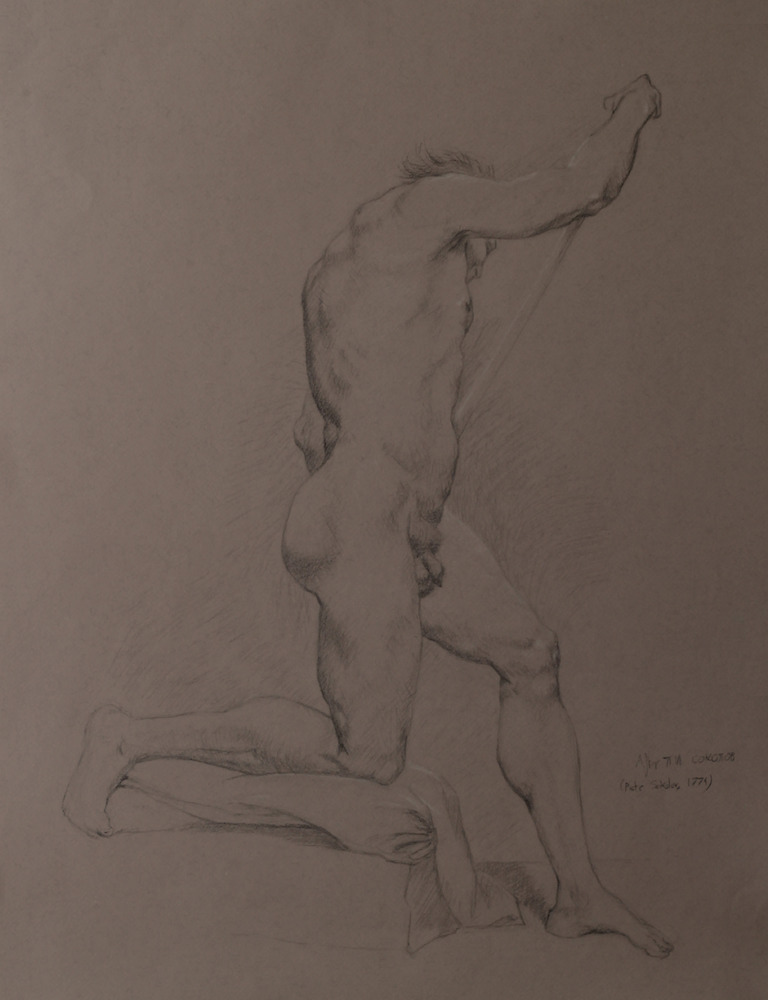

Piotr Sokolov, male model 1774, master copy, Pierre noire and white chalk on toned paper, 2022

by

M. Bivert

Besides, if you intend to use Bargue’s plates as an important part of your training, you may want early on, first at a lesser pace, to

- draw from casts;

- draw from life;

- copy more polished drawings, e.g. Drawing Samples for Copying / Obraztsy Dlya Kopirovaniya by V.A. Mogilevtsev, and more generally, high-quality drawing compilations by established professionals;

- do studies in ink, on any non-erasable material;

- look for other books, tutorials, and compare various artists’ approaches;

- etc.

As you’re getting comfortable with Bargue, you may want to put more and more emphasis on such other things.

Comments

By email, at mathieu.bivert chez: