Maybe you’ve been studying simplified anatomy/mannequinization, got yourself a virtual 3D model, bought a old school wooden mannequin, or a fancier one, perhaps convinced by some great, dynamic pictures.

Basic wooden mannequin

by

Hannah Alkadi

Ink on toned paper, likely in preparation of a painting, mid 1500s

by

Luca Cambiaso (1527 – 1585)

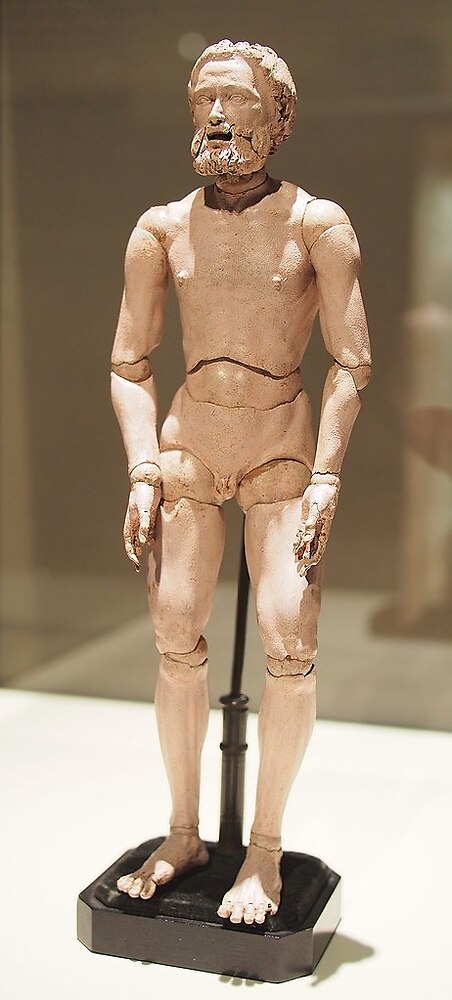

Lay figure made by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) c. 1525, 28cm, Prado Museum, Madrid

by

Luis Fernández García

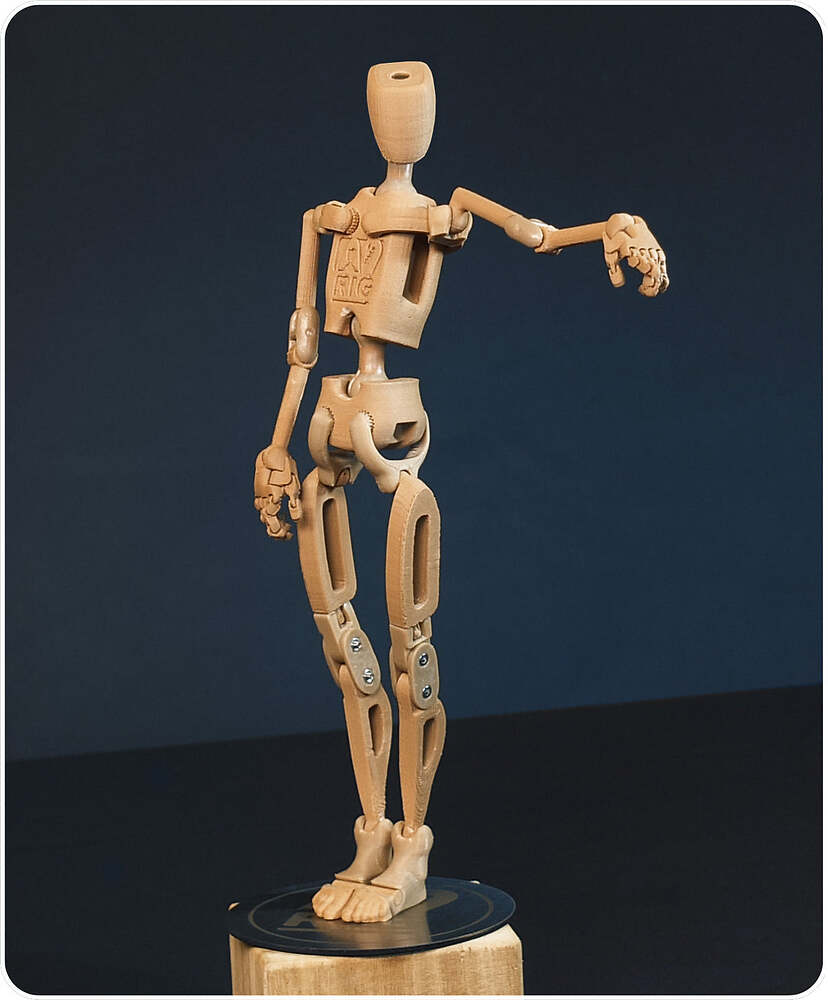

Modern, sophisticated wooden mannequin by Armature Nine through armaturenine.com – likely, available for fair use

You go home, and surprise, the hips joints of the wooden mannequin aren’t moveable. Or, regardless of the mannequin, it doesn’t seem to be willing to take an appealing pose.

What’s happening?

Essentially, what you’re missing (if that happens to you) is gesture, that is, your poses aren’t composed. When a (real) person takes a pose, gravity acts on his body, and to keep equilibrium, the body naturally balances its main volumes. While doing so, it will create a few pleasant composition lines throughout the figure.

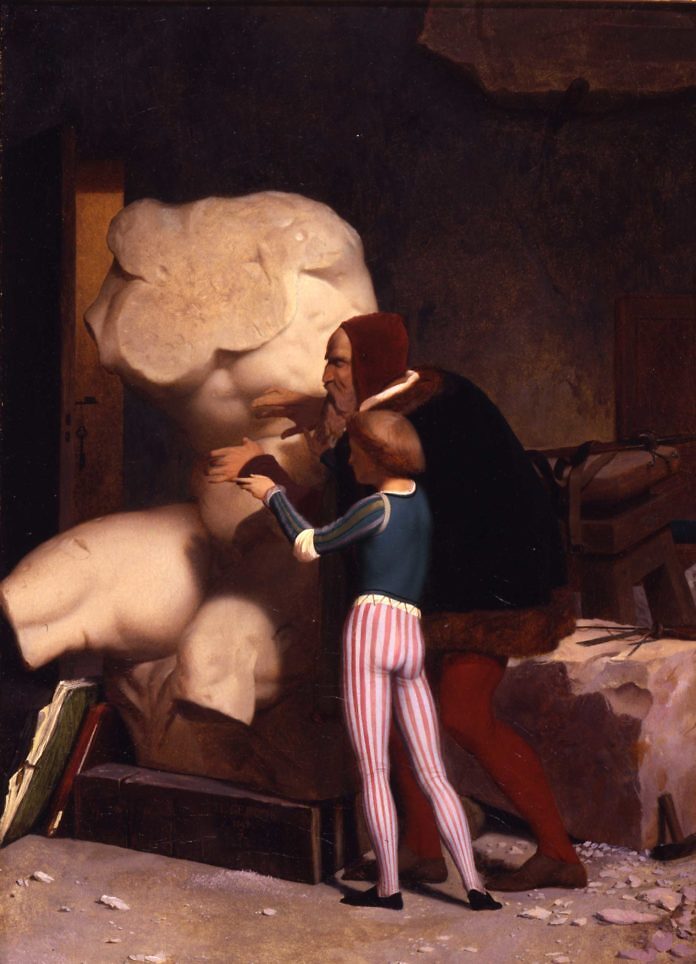

Michelangelo being shown the Belvedere Torso, oil on canvas, 1849, Dahesh Museum of Art, New York

by

Jean-Léon Gérôme

But when you’re posing a mannequin, whether real or imagined, there’s no natural balancing of those volumes because of gravity, so unless you explicitly look for those composition lines or unless you’ve got some good instinct for that, your pose will lack appeal.

Some authors recommend to regularly make hundreds of quick “gesture” drawings: a goal of such drills is to help you unconsciously absorb the kind of rhythms occurring when posing in the human body, and how to simplify them efficiently.

Then, for instance when working from imagination, you can either try to sketch those rhythms lightly first, and then build your main volumes on top, or if you don’t want to sketch them explicitely, have them in your mind’s eye when developing the volumes. When working from physical mannequins, take the time to make sure they do mimic realistic poses, to the best of the possibilities offered by the mannequin.

Note: In summary, a mannequin is yet another tool, and as for any other tool, there’s a learning curve. It’s important to understand the possibilities and limitations of your mannequins: it’s not because they can’t achieve all poses a human can that they are to be systematically discarded for instance.

Note: There are a few common drills often suggested when working with mannequins, such as:

- pose it one way, but draw it by placing yourself in your mind’s eye at a different point of view than where you sit relative to the mannequin. Once you’re done, you can turn place yourself where you imagined to be when drawing, and compare your result with the model;

- a variant would be to lit it one way, but to change the lighting direction;

- it could also be used to practice drawing from memory.

For more on such learning technique, you may want to have a look at this article on “advanced” usage of Bargue’s drawing course

Comments

By email, at mathieu.bivert chez: