We argue that what we call the “academic block-in”, which mainly consists in indicating the main volumes of a subject on a sheet of paper, through a set of lines, often mostly straight nowadays, is actually a refined grid system, that may sacrifice a bit in accuracy to greatly improve fluidity and speed, thus making the drawing process more enjoyable.

This point of view may help people overusing grid systems; this article assumes the reader has at least some experience with drawing.

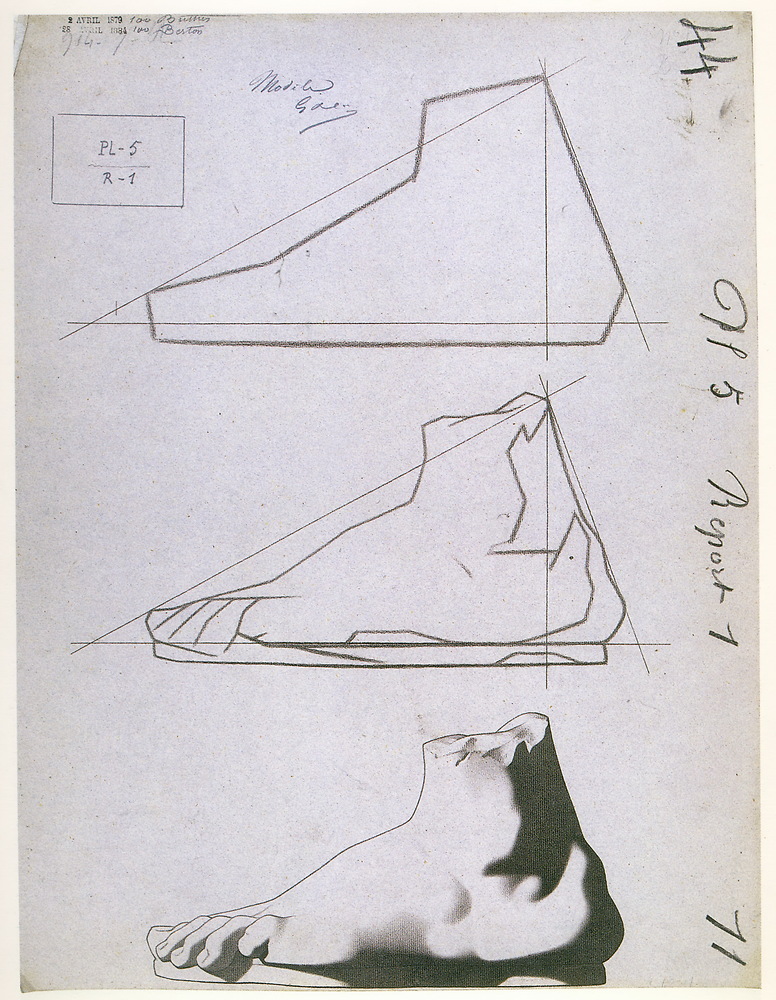

Plate I 5, Profile of a foot

by

Charles Bargue

The grid system

Since at least the Renaissance, grid systems have been used to help painters reproduce what they perceive with great accuracy. From a pragmatic and practical point of view, such devices are useful to reduce the subject’s sitting time, or to capture restless subjects, such as a busy children.

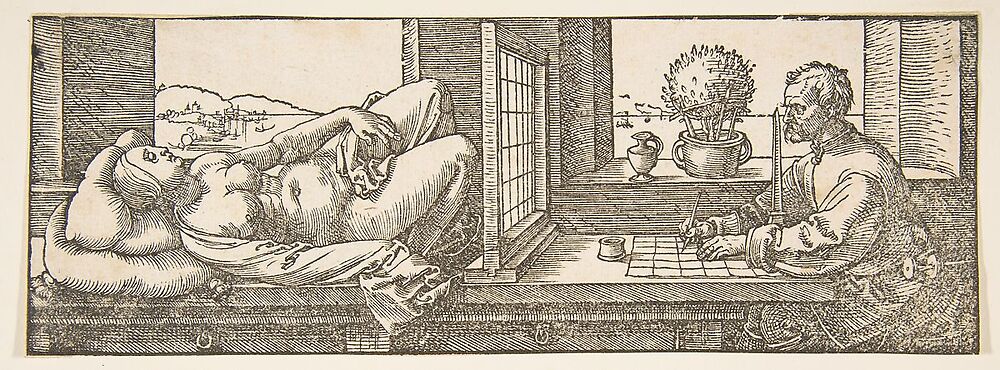

Draughtsman Making a Perspective Drawing of a Reclining Woman, c. 1600, woodcut

by

Albrecht Dürer

Such systems also naturally provides a way to enhance or reduce the size of a drawing, by multiplying or dividing the size of the squares: a small figure drawing on a sheet of paper can become a greater than life figure on a fresco.

The following exemplifies such usages; note the barely visible grid on the drawing:

Preparatory drawing for the Sibyls fresco in the Chigi Chapel of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo, depicting the prophets Hosea and Jonah

by

Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio)

The Sibyls fresco in the Chigi Chapel of the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo

by

Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio)

There are however, a few issues:

- it requires additional material, and a specific setup;

- it may need to be optimized with a local second grid to help capture more details, for instance the facial features on a figure drawing;

- on the contrary, it may be too fine for other areas, in which case it may need to be relaxed so as to be more efficient;

- it’s mechanical, thus in essence opposed to a more creative, intuitive, fluid process;

- in the hand of an experienced artist, it’s rather slow and clumsy, by comparison with an academic block-in;

- while it can give a sense of confidence to beginner artists, it can actually hinder their progress, by establishing a comfort zone.

Note: Nowadays, the advantages of grid systems, of great value for professionals, are obtainable with much less effort, through the use of cameras and projectors.

The academic block-in

To fix ideas, let’s consider the case of a standing figure; the argumentation would still hold true for other subjects, with minor adjustments.

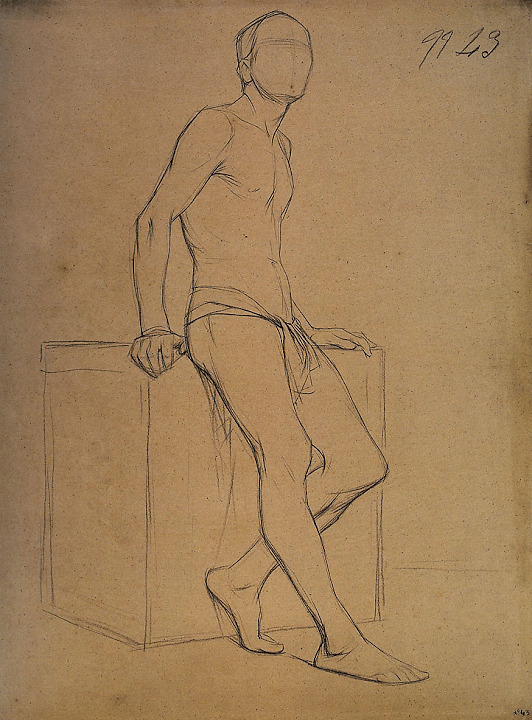

Plate III 43, Man leaning against a stand, face lifted up

by

Charles Bargue

Different authors will use different approaches, but in essence, they mostly all start by indicating the top and bottom of the figure on the sheet of paper. They can now ensure that the sheet is large enough to support the whole figure.

Then, they can divide that distance in two, in three, in four, and see if there are any major points matching on the figure. Or, use the head’s height as a unit of length to measure the figure as a whole and its parts. Then,

- correlating those vertical distances with horizontal ones;

- using a few (vertical) plumb lines and horizontal alignments lines;

- some angles measurements;

- simplifying small line variations with a single straight line;

- etc.

Will all give enough information to place the main volumes of the figure with respectable accuracy. As for grids, the process can be recursively applied locally to help increase the accuracy, for instance on the face.

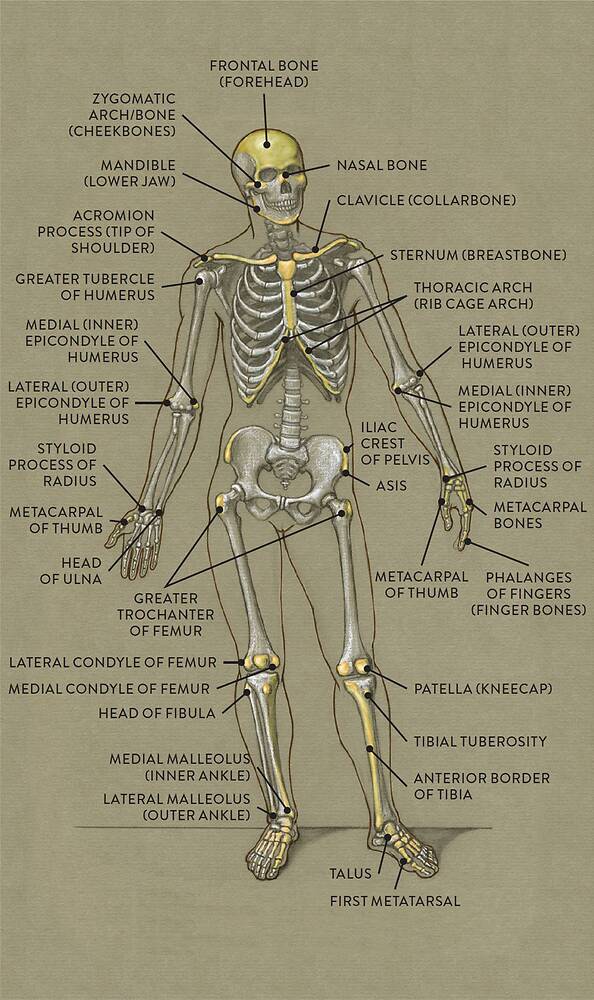

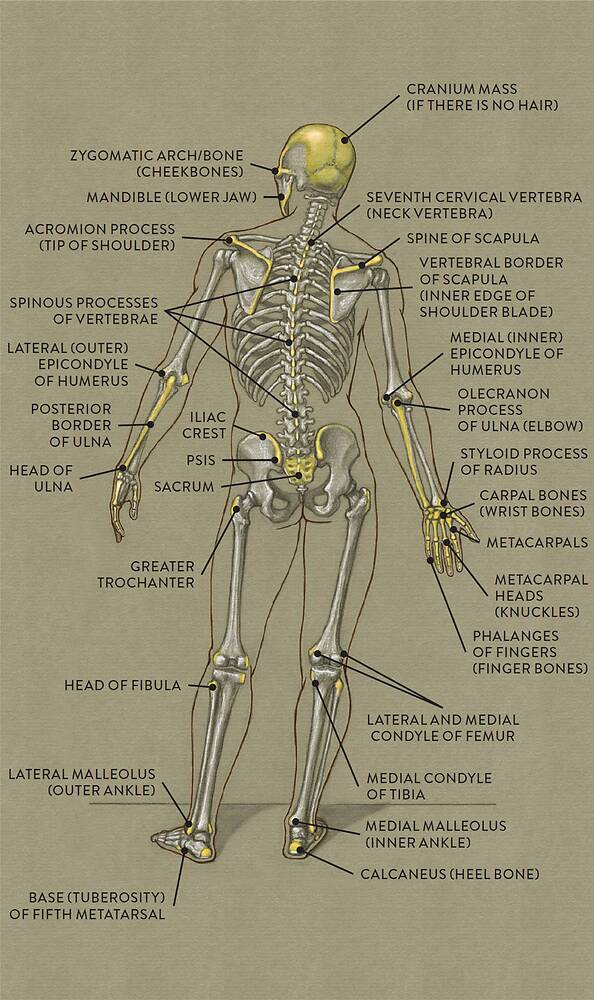

Note: Anatomical informations can also be placed at that point, especially bony landmarks, or the medial plane, as they will help to place the body’s main volumes “in space”. When drawing from life, the model will naturally move and will need to take breaks: such fixed anatomical knowledge will help counteract this. A key advantage of using bones is that, with the help of a good anatomical book, muscles' origin/insertion points, which are fixed from an individual to another, can be inferred. Thus, muscles volumes and subtle form variations can be inferred from a skeleton.

Bony landmarks, front view, from Classic Human Anatomy In Motion - The Artist’s Guide to the Dynamics of Figure Drawing

by

Valerie L. Winslow

Bony landmarks, back view, from Classic Human Anatomy In Motion - The Artist’s Guide to the Dynamics of Figure Drawing

by

Valerie L. Winslow

If you pay close attention, dividing distances in equal proportions and using straight horizontal/vertical alignment lines is in essence very similar to using a partial grid. Though, this doesn’t require to explicitly use a grid, and the painter’s mind can be focused on something more enjoyable and creative than mechanically following a grid.

Note: The mindset of a painter can subtly influence some qualities of his creations. For instance, rushed marked or lack of confidence can be felt in beginners’ works.

Note: While the academic block-in can still be used to increase/reduce in size a preliminary drawing, a grid system of a projector may be better suited, this kind of process being nearly purely mechanical. They are so only nearly because from a composition point of view, in the case of some subjects, such as religious figures, an major increase in size can alter their perception by humans.

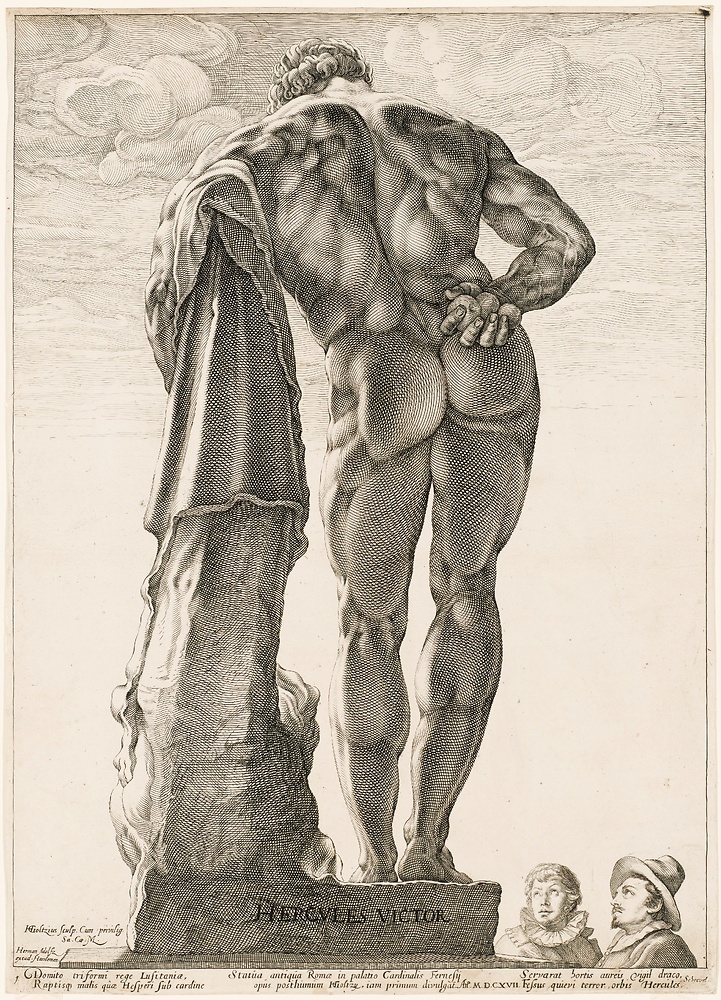

Engraving of the Farnese Hercules by Glycon, likely after a model from Lysippos

by

Hendrick Goltzius

Comments

By email, at mathieu.bivert chez: