Charles Bargue (c. 1826 - 1883)’s drawing course is often used and recommended as a first stepping stone in modern realistic art education.

The course itself, created under the supervision of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824 - 1904), consists of a series of wordless plates (lithographies), divided in 3 sections, which have recently been compiled into a book (pdf) by Gerald M. Ackerman (1928 - 2016), thereby augmenting the plates with some notes, recommendations and models’ pictures.

The upcoming articles are technical, written for self-taught students confused about Bargue plates, or willing to study them most efficiently. This first article introduces the course, and the most common way of studying the course.

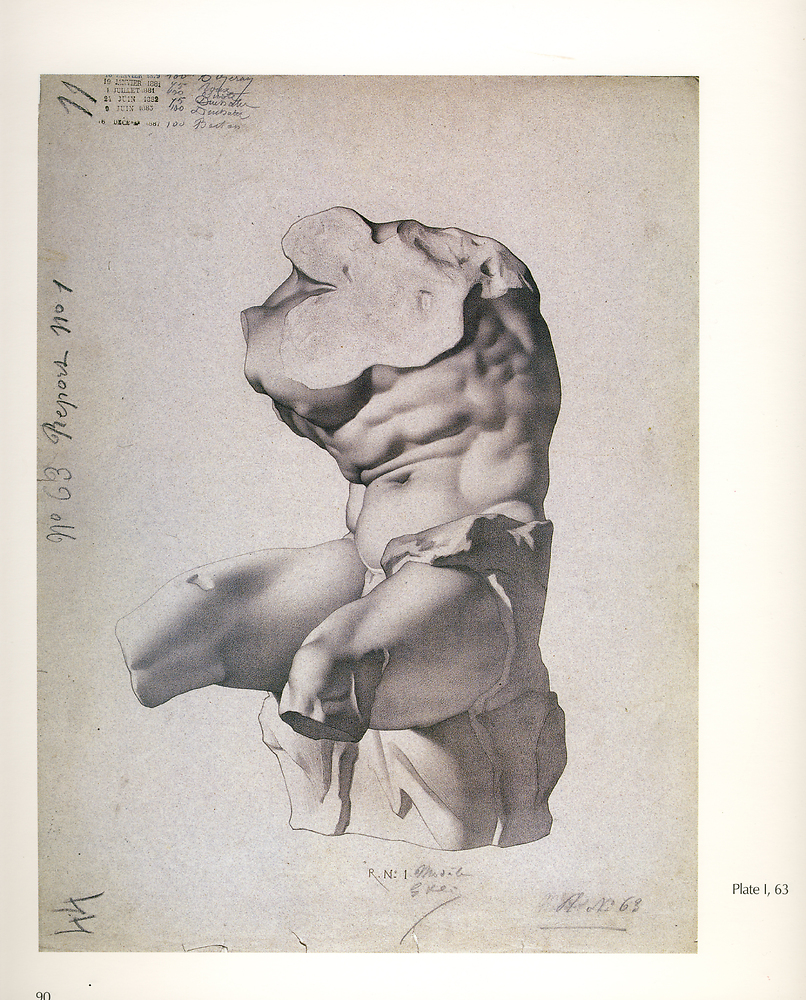

Plate I 63, Belvedere torso, front

by

Charles Bargue

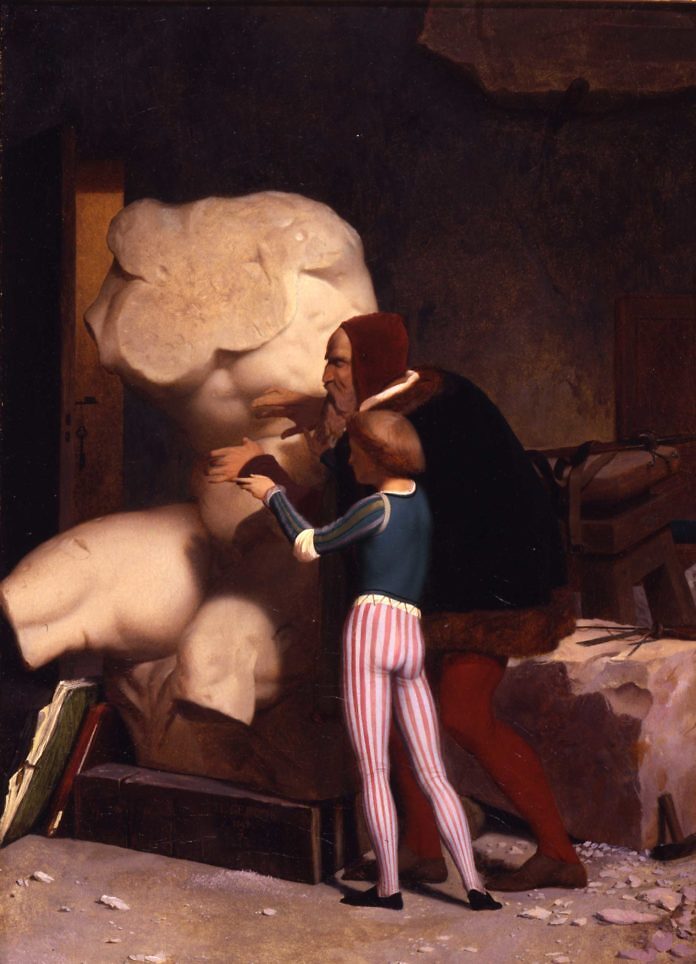

Michelangelo being shown the Belvedere Torso, oil on canvas, 1849, Dahesh Museum of Art, New York

by

Jean-Léon Gérôme

Introduction

Bargue’s plates borrow to one of the most ancient teaching process, already in place in the Renaissance and before, where students are to learn from their masters through copy: master study/copy.

The process is not specific to the West: in China, it was one of Xiè Hè (謝赫) (Liu Song (南朝宋, 420–479) and Southern Qi (南朝齊, 479–502) dynasties)' six principles of Chinese painting (繪畫六法), 傳移 (chúan yí), often translated as transmission by copying:

Note: For earlier examples, see Annibale Carracci’s Scvola perfetta per imparare a disegnare tutto il corpo humano, Odoardo Fialetti’s “The True Method and Order to Draw All Parts and Limbs of the Human Body”, or this list of various drawing treatises from 1400s to 1700s.

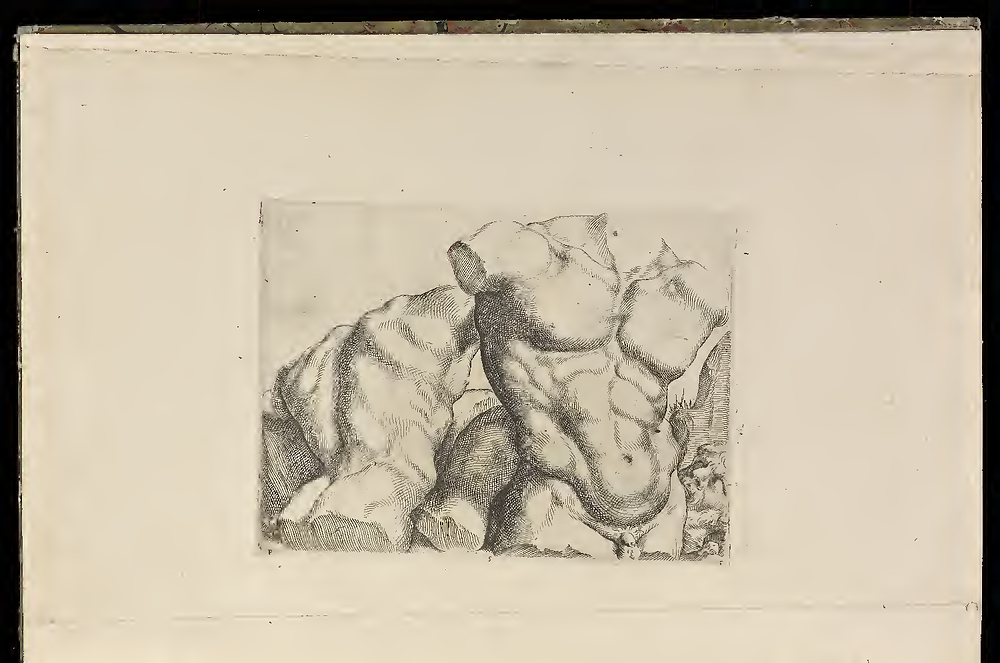

Torso, back & front; page 41 of the Scvola perfetta per imparare a disegnare tutto il corpo humano

by

Annibale Carracci

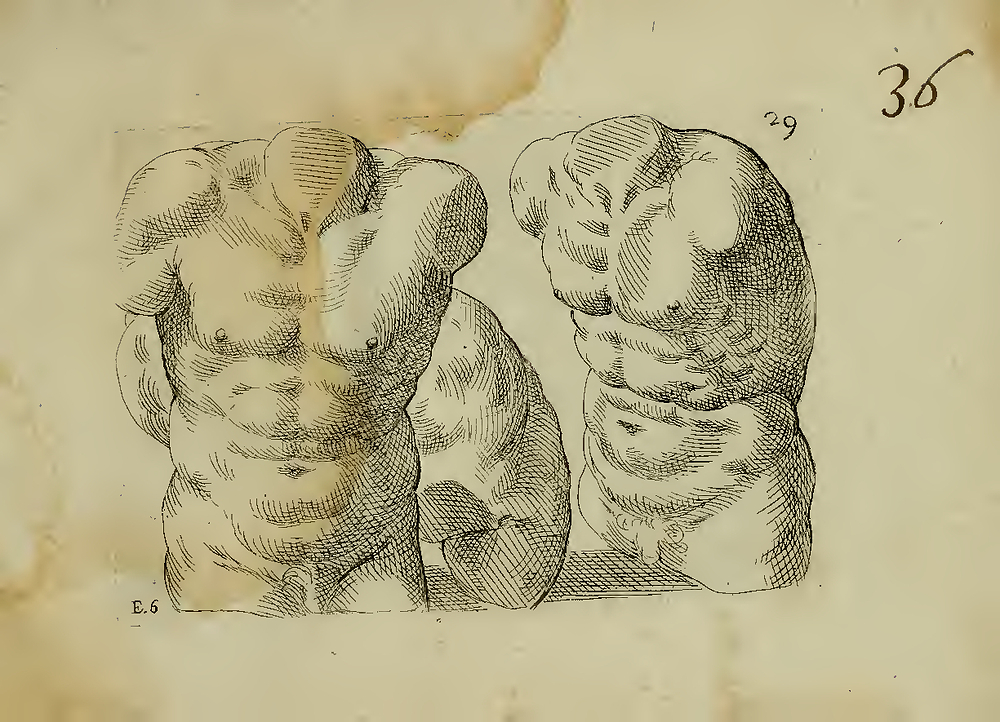

Torso, front; page 61 of the The True Method and Order to Draw All Parts and Limbs of the Human Body

by

Odoardo Fialetti

There’s a common confusion regarding the act of copying in art. Copying in itself bears little artistic value: making a copy can barely be considered creating art. Yet, it’s one of the most efficient way to learn the craft, whether the copy is from a master’s work, or from life.

Note: Likely, the confusion stems from the fact that it requires a bit of education to distinguish between pure technical abilities and artistic abilities, an education that was not systematic, and that seems to have deteriorated with the introduction of “modern art”.

We could draw an analogy with other disciplines: classical musicians practice their scales, boxers, running, mathematicians, the ability to prove well-known theorems; yet, all those are purely technical skills, and cannot be compared with the creation of a symphony, fighting or developing a new field of study.

Also, as for other domains, what one gains from training depends as much on what kind of exercises are performed as much as how they are performed. There is more than one way to run, more than one way to practice scales, more than one way to prove a single theorem, more than one way to copy, and each way will bring different benefits.

The main approach

To my knowledge, we have no record of Bargue’s nor Gérôme’s views regarding the course’s usage, thus leaving us room for interpretation.

Note: Again, this openness in essence is very similar to that we have when faced with interpreting composition or Chinese characters.

Despite the potential diversity in approaches, when people talk of “doing Bargue’s plates”, they often mean to create a precise copy, often using sight-size, of a plate from the first section.

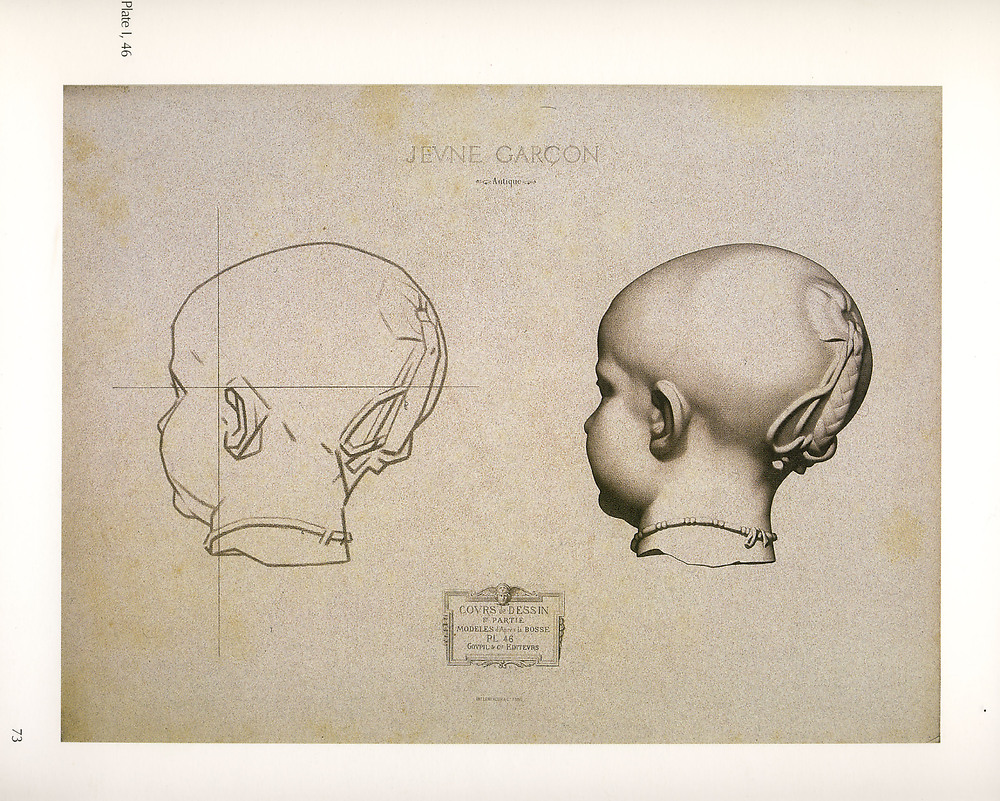

Plate I 46, Antique, Young Boy

by

Charles Bargue

Note: We’ll mainly focus on the first section, and lightly mention the second and the third. We’ll keep the common terminology of assimilating “Bargue’s plates” with plates from the first section. Plates below are typical examples from respectively the second and the third section:

Plate II 54, Study of a baby, litography by Charles Bargue

by

Timoléon Lobrichon (1831-1914)

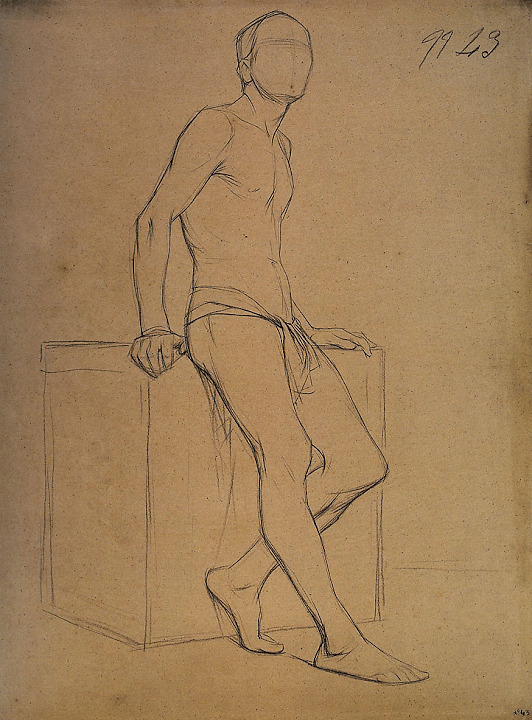

Plate III 43, Man leaning against a stand, face lifted up

by

Charles Bargue

As this approach is extremely common, there’s plenty of extensive documentation on the subject. The goal of this series is to expose content that is often not introduced, so we’ll leave the curious readers with existing documentation from external sources. Nevertheless, we recommend students to keep reading this series at least once before diving in.

Among many others, students can refer to Dorian Iten’s How To Draw What You See guide, relying on a Bargue plate. There’s also Stephen Bauman’s sample “atelier tier” lessons from his YouTube channel, or this series of 30 videos by the Da Vinci Initiative:

Notes on sight-size

For those who have no idea what sight-size is:

Sight-size if often used to copy Bargue plates; some people go as far as to suggest that this was originally intended.

Yet, I would argue against: I think this argument stems from the fact that many plates comes with a block-in and the final drawing, both in a sight-size-like setting. The block-in being strictly proportioned to the original.

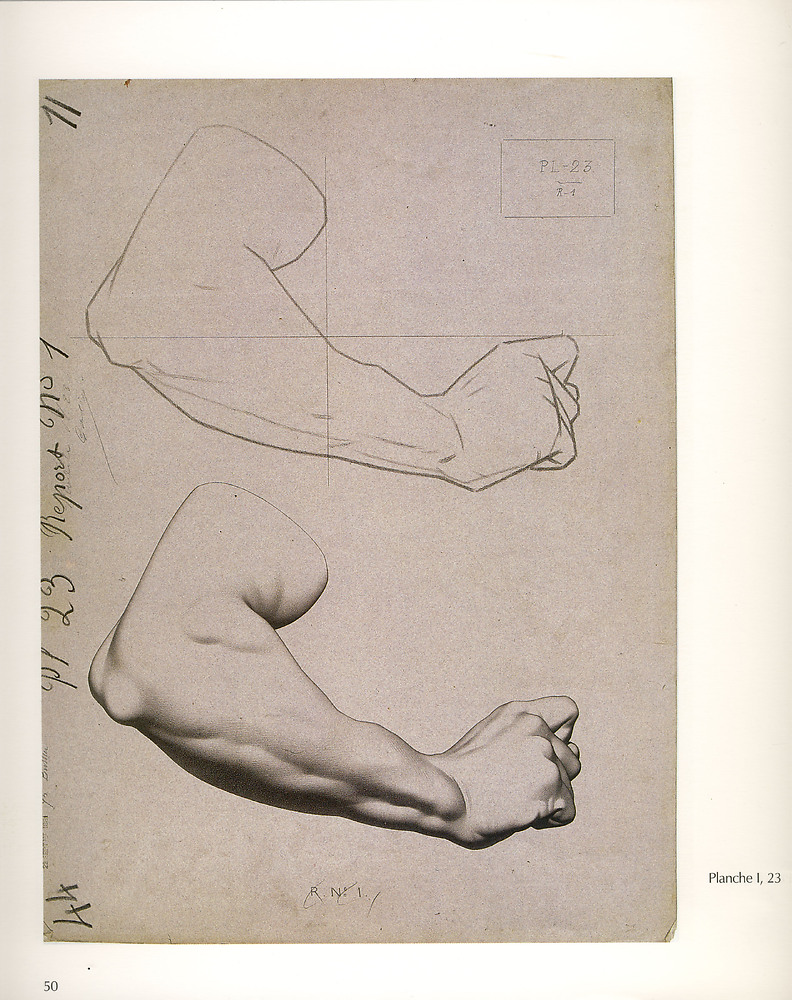

Plate I 23, Man’s arm, bent

by

Charles Bargue

However, this is highly likely to be incidental: if one had to make 70 plates, one is likely to make the block-in from the final drawings, by tracing them afterwards. Putting them side by side would help understand the interest of the block-in, and be aesthetically pleasing.

Note: It’s also likely that the strong emphasis in the main approach in creating a perfect copy is at least partially rooted by that same cause. Yet, contrary to sight-size, aiming at an accurate copy is actually very useful to beginners. We’ll expand on this later.

While sight-size isn’t that bad, I would still recommend using “same-size” instead for beginners, and then to move on to less restricted approaches (essentially, comparative measurements, see this article).

Notes on perfect replica

Most people promoting the main approach with sight-size aim at creating a perfect replica. There are good and bad things here.

The main issue is that creating a perfect replica is mechanical in essence; the easiest way to reach such a goal is to use an extremely mechanical process, with lots of direct measurements. Regarding sight-size, it can be too constraining when working from living subjects for instance.

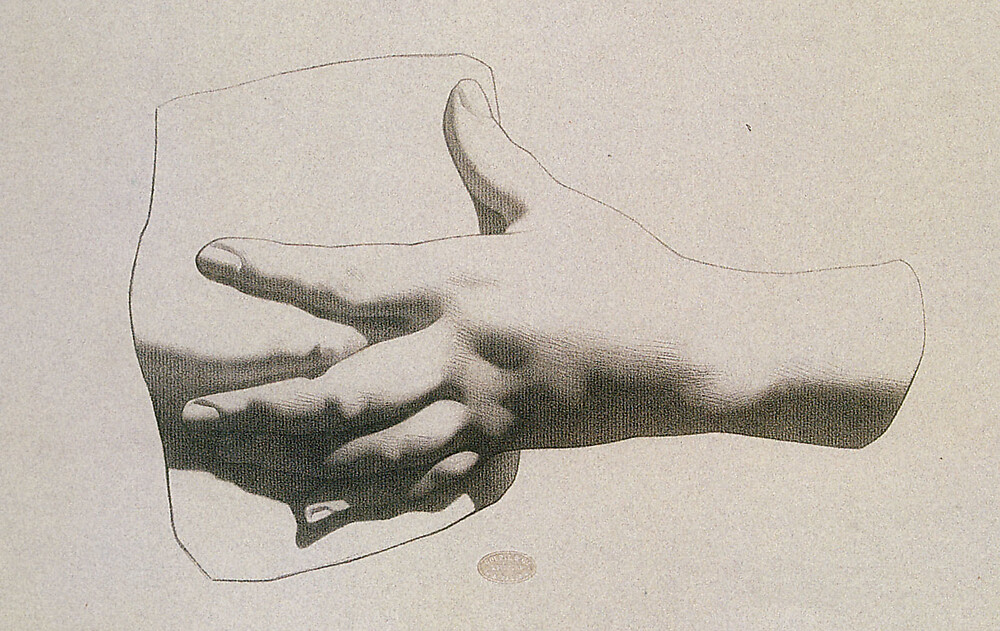

Plate I 15, Hand of a woman pressing on her breast

by

Charles Bargue

On the other hand, not attempting a perfect replica will hinder the assimilation of some elements of the course, as they will go unnoticed (we’ll expand on this later); people can drill dozens of plates without understanding key aspects.

I think attempting a perfect replica once or twice for a beginners, using very mechanical means, isn’t necessarily bad, as it will help to understand:

- how constraining (perhaps even un-enjoyable) that approach is;

- how difficult it is to make precise measurement with a ruler/stick;

- how often one’s eyes actually extremely sensitive and more precise than a ruler/stick;

- how small distance/angle errors can easily stack-up,

- etc.

But this should not become a habit, and students should promptly aim at a looser, more practical approach. Generally speaking, students should strive to be thorough. Not attempting a perfect replica doesn’t mean not attempting to be very accurate either, and I think that’s the best middle-ground for such an exercise.

Comments

By email, at mathieu.bivert chez: