This series is an introduction to watercolor material, with some practical advices on how to use watercolors. This is not an introduction watercolor painting: if that’s what you’re looking for, this article is a selection of YouTube (free video) tutorials and demonstrations, by established artists, that better serves such a purpose.

I try to condense here a few years of experimentation with the medium. Despite being rather extensive, it’s still far from exhaustive; one can refer to Bruce MacEvoy’s website (handprint.com) for a far more complete, encyclopedic exposé.

This first article quickly introduces the medium and distinguishes it from its closest peers (gouache and tempera).

Introduction

Watercolor is a demanding medium, usually considered harder than oils. A likely reason would be that oils can be intuitively controlled like clay, in a way that matches our sense of touch.

Watercolor however requires a different mindset: one needs to think it terms of how water flows, that is, in terms of difference of humidity “potentials”, which is a less intuitive behavior, that does not match our sense of touch.

Artists generally choose to work either in a refined manner, or more spontaneously, with plenty of room for in-betweens, a dichotomy that I explored in the first article of a series on figure drawing. Interestingly, this difference has already been established in water-based traditional Chinese painting; see Gongbi (工筆) and Shuimo (水墨).

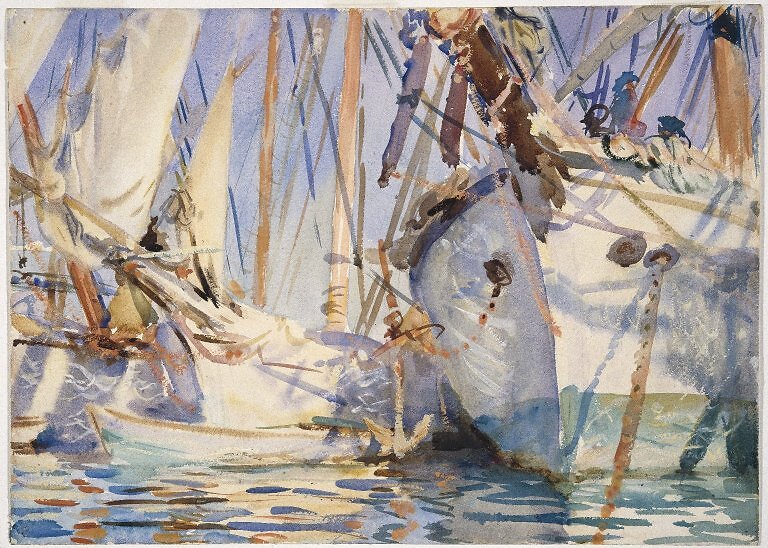

Below, Dürer’s hare is performed with great details/minutia, while Sargent’s is far more “impressionistic”, broad, loose. Both did use opaque paints, an often controversial topic among watercolorists.

Hare, 1502

by

Albrecht Dürer

White ships, watercolor, c. 1908

by

John Singer Sargent

Fine-arts require fine handling of materials, attention to subtleties. Often there are two main factors that differentiate a novice from an advanced painter: the time they spend on an artwork, and their abilities to express themselves with subtlety, finesse, efficiency. While looser approaches may look easier, they tend to require a more delicate handling, and a strong focus on essential aspects, such as composition, color harmony, mood, while minutious approaches are often technically easier, repetitive, but more demanding patience-wise.

Paint composition

Most paints are composed of finely ground pigments particles, glued together by a binder. In the case of watercolor, gum arabic is often used as a binder, but modern synthetic products such as methyl cellulose can also be used.

Pieces and powder of raw gum arabic

by

Simon A. Eugster

Some additives can be added to either reduce manufacturing costs, or to alter the paint’s usability. In watercolor, honey or glycerin can be used to keep the paint moist, additional gum arabic can help to increase brilliancy. Lower quality paints may contain fillers, such as kaolin (white clay), that will lower the paint’s tinting strength when mixed.

Bruce MacEvoy covers here the influence of particle sizes, pigments concentration, etc. and here various aspects of paint’s composition.

The video below, sums-up the paint creation process by Old Holland; while mainly focused on oils, things are similar for watercolors, and for other manufacturers of course. The second one highlights Daniel Smith’s Lapis Lazuli.

Watercolor, gouache, tempera

Among the three, “genuine” egg based tempera is the most special: it uses egg yolk as a binder (there are variants) and typically involves a unusual, refined painting process (see CXLVII, How to Paint Faces) of layering cross-hatches. It was traditionally used to paint Christian icons in the Middle-ages.

Egg yolk being an emulsion of oil and water, tempera is at the frontier between oil paints and water-based paints.

Tip: Adding a bit of egg yolk to some out-of-the tube oil paint will “create” a water-soluble oil paint. Be mindful of the impermanence of fresh egg yolk: a few drops of clove oil can help.

The following demonstrates hand-made paint with a “varnish-mayonnaise”, greasy tempera, by Pietro Annigoni, the now deceased tutor of Michael John Angel, head of the Angel Academy of Art (Florence, Italy):

The differences between watercolor and gouache are more subtle: particle size, pigment concentration, pigment’s qualities, painting process, artwork’s “nature”. For more, see:

- What’s the difference between watercolor and gouache?, questions from James Gurney to Winsor & Newton and Holbein;

- Gouache Ingredients: Info from Manufacturers, again by James Gurney;

- Gouache and bodycolor (handprint).

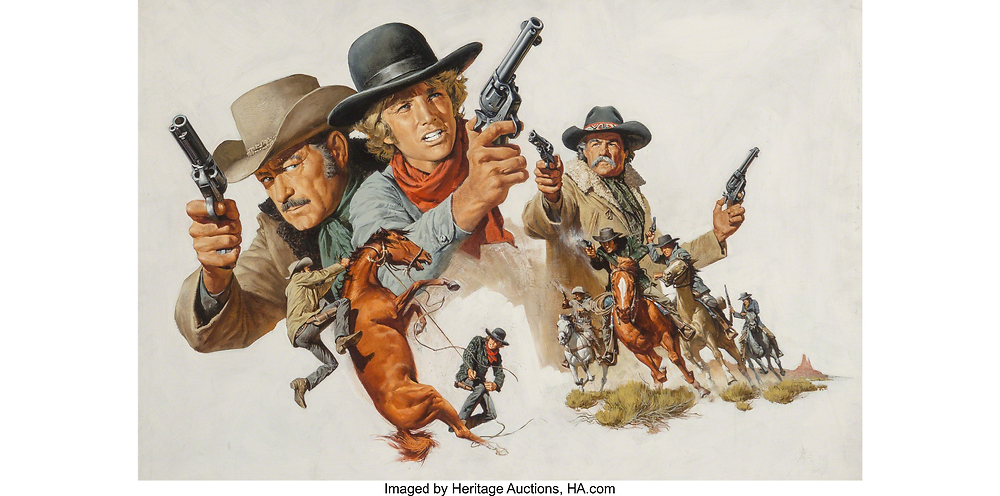

In short, gouache is often used opaquely: which is achieved via coarser pigments, (hence requiring less manufacturing effort, hence why it often costs less than watercolor) and by a greater concentration of pigments, and/or of fillers (the later being used for lower quality paints). “Historically”, gouache was often used within the entertainment industry, such as for movie poster (see poster paint), where the art aims at being photographed and reproduced rather than kept: the pigments don’t have to be as permanent as they have to be for more regular artwork.

Note: Gouache can be used transparently as well as opaquely, and often rewets nicely enough to be used as a cheaper alternative to watercolors.

Wild Rovers movie poster, reproduced by Heritage Auction, gouache on board

by

Frank McCarthy

Comments

By email, at mathieu.bivert chez: